There’s only one book in the world, and that’s the one

everyone accurately misquotes.

—Allen Curnow, ‘An Incorrigible Music’

An admission: these are not the works by Denys Watkins that I was expecting to include in Fluid structures. For a couple of years now, I have admired Watkins’ largely abstract paintings, works populated by organic shapes that evoke, among other things, the alien structures viewable only with the most powerful of microscopes: bacterial rods, flagellal threads, nucleic and mitochondrial disks. Watkins has made watercolours in this vein, and these are the sorts of works I had in mind when I asked him to participate in the show. But eschewing such biomorphic images in favour of the more regularly geometric ones displayed here felt like an appropriate decision, since one of the great pleasures of getting to know Watkins’ work is constantly being surprised, constantly having one’s expectations exceeded.

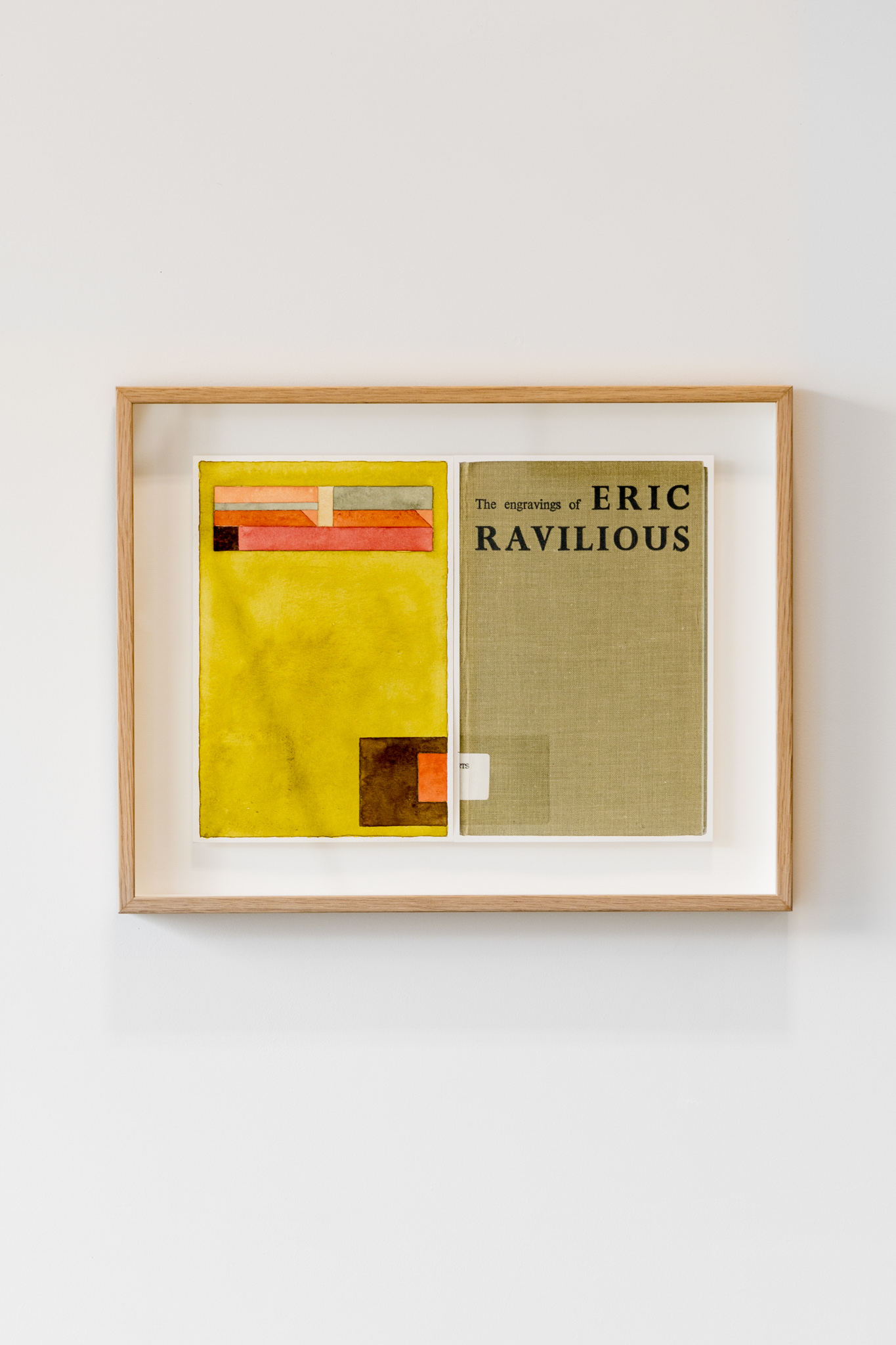

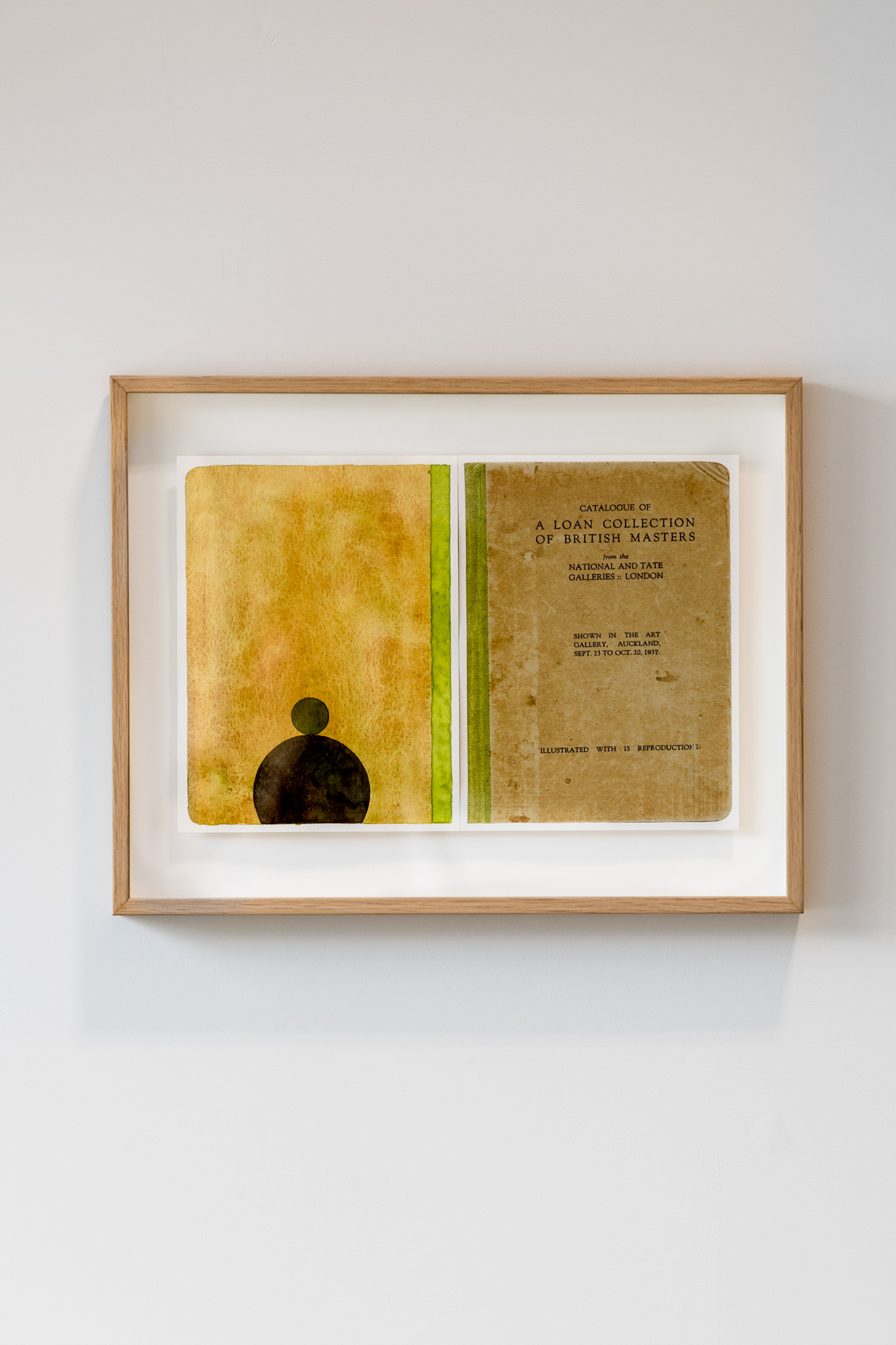

Restlessly experimental, Watkins’ work spans a wide range of media, encompassing prints, assemblages, and kinetic sculptures, in addition to a variety of paint-based techniques. In his image-making, he has flirted with diverse styles and modes, sampling and blending surrealism, pop, and text-based art—seldom solely figurative, seldom completely abandoning real-world references. The references for the works in this show are of course book covers, which appear in the works themselves as digital prints. A watercolour by Watkins sits alongside each cover, mirroring its overall format. Sometimes the correspondence is close, as in Wisdom. Sometimes it is looser, as in Eric. Purged of any text, the watercolours bear a family resemblance to the covers, but they are never their twins.

Denys Watkins, Eric, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and Parlour Projects, Heretaunga Hastings.

Watkins’ use of book covers is a reflection of his long interest in, and respect for, design practices, including typography and book design.[1] One could also interpret it as a subtle statement that print and material cultures ought not to be considered in isolation from the so-called ‘fine arts’, since these disciplines are all intimately bound up with the historical moment, and with that moment’s aesthetic and ideological concerns. Wisdom in particular would seem to support this understanding, incorporating as it does a strident pattern that might equally be found on a poster, a ceramic jug, or a piece of fabric. The work reminds us that ‘interdisciplinarity’ is far from new, calling to mind the furious exchange between modernist designers and artists, whether those associated with the Bauhaus, Bloomsbury, or—here in New Zealand—the Group in Christchurch.

The books chosen by Watkins are surely also significant in terms of their contents, but quite how we are to read them is not immediately clear. At first glance, they seem anachronistic. This is especially true of the publications that form the basis of Eric and Loan Collection: a 1946 book on the comparatively little-known English artist Eric Ravilious, and a catalogue for an exhibition of ‘British Masters’ that visited Auckland in 1937. Both came from the Fine Arts Library at the University of Auckland, a fact hinted at by the reinforced spine and the printed label. Such books are not esteemed today. We dismiss them for their unglamorous subjects, the limited number and quality of their reproductions, the perceived datedness of their texts. It is thus tempting to think of the books in Watkins’ works as inevitable casualties of the march of time, destined to be shifted to offsite stacks or deaccessioned altogether.

But although Watkins is unquestionably a witty artist, and his humour often dark, I find myself thinking of his diptychs as expressive of a genuine affinity for the subject matter of the books. There has lately been something of a revival of interest in Ravilious, who worked across a variety of disciplines, including painting, engraving, and design. One can picture Watkins poring over the publication, extracting elements of value with which to enrich his own multifarious practice. Then, too, one can imagine him leafing through the British Masters catalogue with enthusiasm, considering the specific works from the National and Tate Galleries that Aucklanders had access to that spring 80 years ago. What artists and works in our local history might bear the influence of those visitors from abroad?

Denys Watkins, Loan Collection, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist and Parlour Projects, Heretaunga Hastings.

It may seem trite to say it, but books, like other works of art, are a means to discovery. For people based in Aotearoa in the years before cheap flights and the internet, they were perhaps the primary way of finding out what was going on beyond these islands. Watkins has spent a large amount of time looking at books, not least because he has taught for many years at the University of Auckland, and—as anyone who has worked for a tertiary institution will confirm—one of the greatest perks of the job is the library card. We are fortunate that these works not only reflect Watkins’ incorrigible curiosity, but also provide us with rich material for discoveries of our own. Consider Loan Collection, with its spectral circles of deep green and black, looming against a mottled brown that so perfectly evokes the ageing of once dove grey board. It’s the work of a master, whose misquotations are, in their own way, absolutely right.

*

Text written to accompany the exhibition Fluid structures. Learn more and read other essays via Parlour Projects.

Fluid structures: watercolour group show

Curated by Francis McWhannell

With essays by Lucinda Bennett, Francis McWhannell, Tendai John Mutambu, Linda Tyler, and Victoria Wynne-Jones

24 March to 22 April 2017

Parlour Projects

Heretaunga Hastings

[1] It worth noting that Watkins’ undergraduate studies at the School of Design, Wellington, were in graphic design (he subsequently studied fine art in London at the Central School of Art and Design and at the Royal College of Art) and that a strong design sensibility runs through all his work.