Discovery

When I take the Broadsheets out of their museum boxes, the covers are familiar. I open one and brush my thumbs over the pages. The newsprint is velvety. I think of the strange little patch of downy fur at the base of my newborn baby’s back. I put my face to the magazine and breathe in. It smells as sweet and musty as the inside of my mother’s room.[1]

—Tusiata Avia

On the kitchen table that doubles as my desk lie two books. The first is A Women’s Picture Book: 25 Artists of Aotearoa (New Zealand), published in 1988. The second is the catalogue for the 2014 show Five Māori Painters, curated by Ngahiraka Mason, at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Each is in its own way trailblazing. A Women’s Picture Book overtly centres women. Most are Pākehā, for reasons detailed in an afterword, and a number are lesbian.[2] Five Māori Painters quietly centres wāhine Māori. As I read the words and scrutinise the images, I am reminded forcefully of the limits of my knowledge. Content and context are not entirely unfamiliar. I have some awareness of the collective Haeata, the exhibition Karanga Karanga, the imprint Spiral, the periodicals Antic and Broadsheet, the Women’s Gallery—some awareness, but not a lot.

The happy corollary of recognising my ignorance is contemplating how much I have yet to discover. Discovery is, of course, a fraught notion, bound up as it is with accounts of men like Abel Tasman and James Cook. We know by now that there was nothing new about ‘New Zealand’, at least not to the extraordinary seafarers of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa, whose consummate science had long before allowed them to make guides of the star-studded skies and networks of the island-studded waters. The term ‘discovery’, however, can be useful. It evokes the thrill that drives so much learning. It expresses the feeling I get when I encounter an artist or an artwork for the first time. I have originated nothing, invented nothing. The entity already exists. It is not new. But it is new to me. The feeling is electrifying, and it is one that Gina Matchitt’s Autonomous Bodies seems keen to elicit.

The exhibition emphasises works by non-male artists that may be understood to express non-male perspectives. Although my experience of my gender is not well captured by the binary, I tend to identify as male. Consequently, when Matchitt invited me to write for this catalogue, my immediate thought was that my voice was not the most necessary or relevant one. At the same time, I wished to contribute. I admire Matchitt, both as an artist and as a curator, and I relished the opportunity to work with her. I believe firmly in the value of projects that attend to those who deserve more support, promotion, and celebration than they have historically received. I conveyed my interest and my reservations, secretly hoping that Matchitt would give a reason for my selection. She simply confirmed her enthusiasm. I decided to accept the assignment, but the question of the purpose of my role has lingered in my mind.

I have faith in the potential of ‘allyship’ to further positive change. As a person who enjoys multiple privileges, being Pākehā and not living in poverty or precarity, I aim to be reflective and seek ways of moving more carefully and gently through the world. I wish to speak up and step up when called to, without drowning others out or robbing them of platforms. Allyship is not—to state the obvious—something that an individual achieves or completes. Like gender equality and decolonisation, it is a project that spans generations and requires embodiment by a great many of us to keep growing. It is optimistic, presupposing the possibility of change, and realistic, since it is predicated on the human propensity for empathy across difference.

It occurs to me that Autonomous Bodies is underpinned by similar principles. It reflects considerable and gathering gains made over the past 50 or so years: the expansion of popular notions of the parameters of womanhood and femininity; the interrogation and even prising apart of the gender binary; the movement of communities long marginalised towards the centre. Yet the show is not essentially about triumph. It acknowledges social change, and the activist artists who fight for the same, but it does not presume or argue for an end point. Instead, it invites us all to inhabit ourselves with greater criticality, and to consciously foster the development of richness and texture. It is a show by and about people other than men, but men are welcome as guests. Men are wanted as support people and credited with the capacity to care about intimates and strangers alike. Men are among those who have the most to discover.

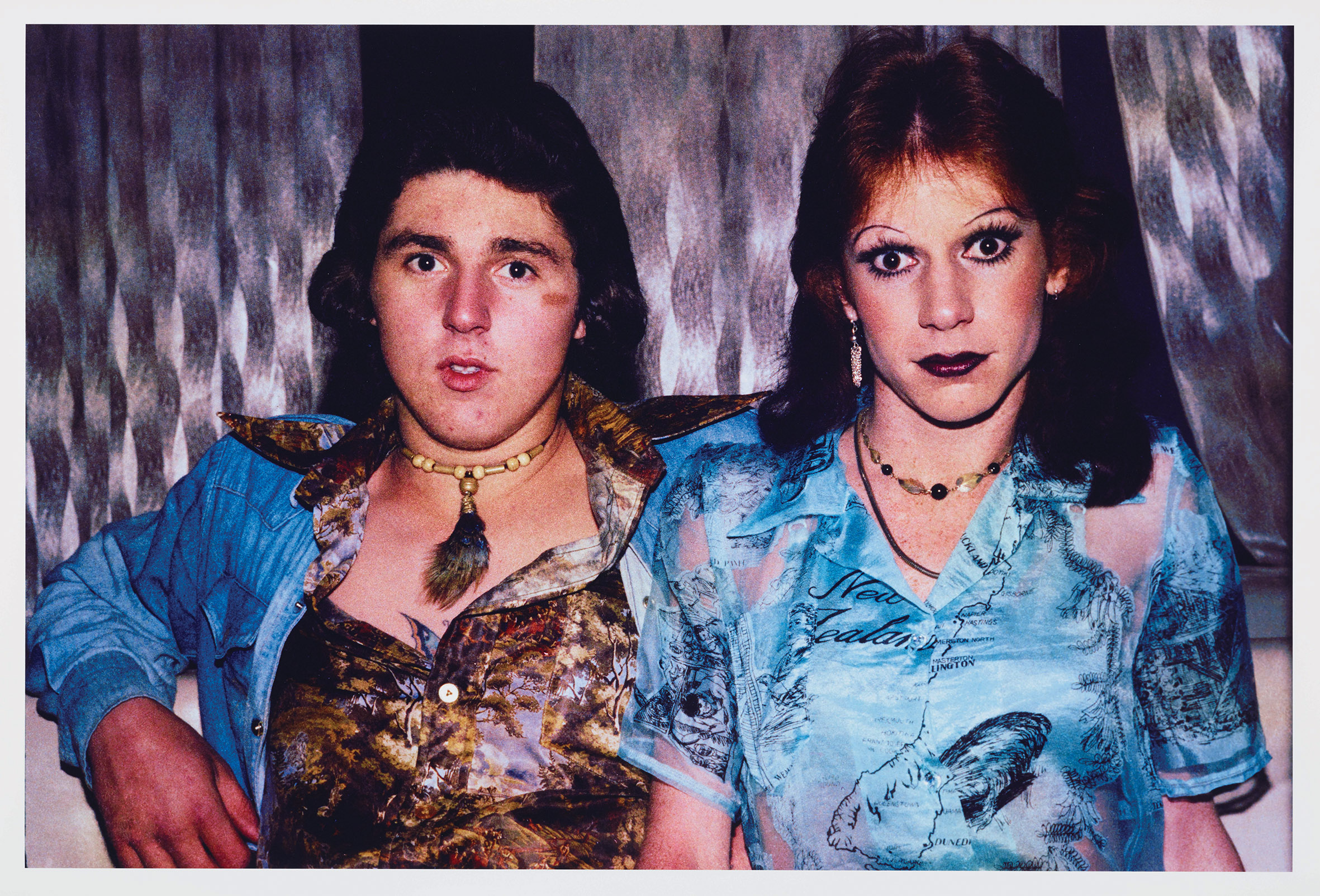

Fiona Clark, Donna Terri and Friend at Mojo’s, 1975. Collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

Correction

I used to have a saying on my wall: ‘Once I was a tomboy and now I’m a full-grown lesbian.’ One day I crossed out the last half and wrote ‘but now I’m queer’. Even that label will probably change.[3]

—Fiona Clark

In Autonomous Bodies, pictures made by men exist as foils. The main characters, or the gemstones, are works by women and non-binary artists. The earliest is a 1975 photograph by Fiona Clark, Donna Terri and Friend at Mojo’s. Clark has noted that Mojo’s, situated on the corner of Queen and Wakefield Streets, ‘was really the only drag performance club’ in Tāmaki Makaurau.[4] At the time the photograph was taken, sex acts between men were illegal and trans identities were often conflated with homosexuality. The tones of the photograph are distinctly 1970s. So are the clothing, hair, and makeup of the subjects. But something about the mood is startlingly contemporary. I fancy that the figures are sizing me up, and asserting that the world through which I move as a queer person is one that they helped to shape.

Clark has commented of her photographs, ‘The people in them are dignified and they are just as comfortable looking at you as you are looking at them’.[5] Encountering Donna Terri and Friend at Mojo’s, I feel challenged, especially by Donna, the woman on the right, with her wide staring eyes. Her black cherry lips seem to ask, ‘How sure of yourself are you, really?’ She wears a short-sleeved blouse of pale blue. It is printed with a map of New Zealand and a kiwi, both disrupted by the cut of the garment. The pattern is kitsch. It might well derive from a Kiwiana tea towel. It evokes a bland, staid middle New Zealand to which Donna ostensibly does not belong. I imagine that she is asserting her connection to this place, regardless of the hostilities she faces from individuals and institutions alike.

Looking at the map, I recall Matchitt’s reflections on ‘early voyagers’ from Europe, like Tasman, Cook, Louis Isidore Duperrey, and Jules Dumont d’Urville. I think of the first European charts of Aotearoa, barely more than coastlines, and the settler colonial projects that such maps were intended to facilitate. The coloniser surveys the land so that it can be seized and divided. Provinces are drawn to be governed, parcels to be sold. A similar act of circumscription is performed on the people. The coloniser sketches them, gets down a general form. To depict is to claim a measure of knowledge. And once the coloniser thinks they know someone, it is so easy to assume superiority. Never mind the details missed or obscured by the outlines laid down. The coloniser colours them in with their own prejudices and fantasies.

Yuki Kihara, who works in Aotearoa and her birthplace of Sāmoa, questions misconceptions and teases out latent texture. Her 2004–5 photographic triptych, Faʻafafine: In the Manner of a Woman (the subtitle translates the title), points to complex understandings of gender and sexuality in Sāmoa that have long been threatened by colonial dogma. Using her own likeness, Kihara plays with stereotypes of the ‘dusky maiden’ and the highly sexed Pacific woman. The work resonates not only with images associated with European voyages, but also with photographs of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There is an especially strong connection with the work of the Pākehā New Zealander Thomas Andrew, who lived in Sāmoa from 1891 to 1939. His career testifies to the strong interest of New Zealand in Sāmoa even before the former occupied the latter in 1914, and before the rise of labour migration from Sāmoa in the mid-20th century.

Faʻafafine parodies romantic, eroticised pictures of the sort taken by Andrew—the combination of potted plants, painted backdrop, mat, and chaise longue emphasising their artificiality. The work also critiques suites of images of indigenous women by photographers like the Australian Charles Bayliss, in which the subjects are shown in varying degrees of undress. Kihara moves from ‘grass-skirted’, to naked, to exposing her penis. By her pose, she recalls Venus, that well-worn excuse for showing a sexualised woman in the Western tradition. She has the self-possession of another figure, herself linked to art historical Venuses: the sex worker in Édouard Manet’s Olympia of 1863. I think of successors of Manet with an appetite for the ‘exotic’ and ‘primitive’, such as Paul Gauguin and Pablo Picasso. Over the centuries, countless Europeans have pictured Moana (Pacific) people. Their often-perverse visions have flowed round the world. Now, Kihara directs the course.

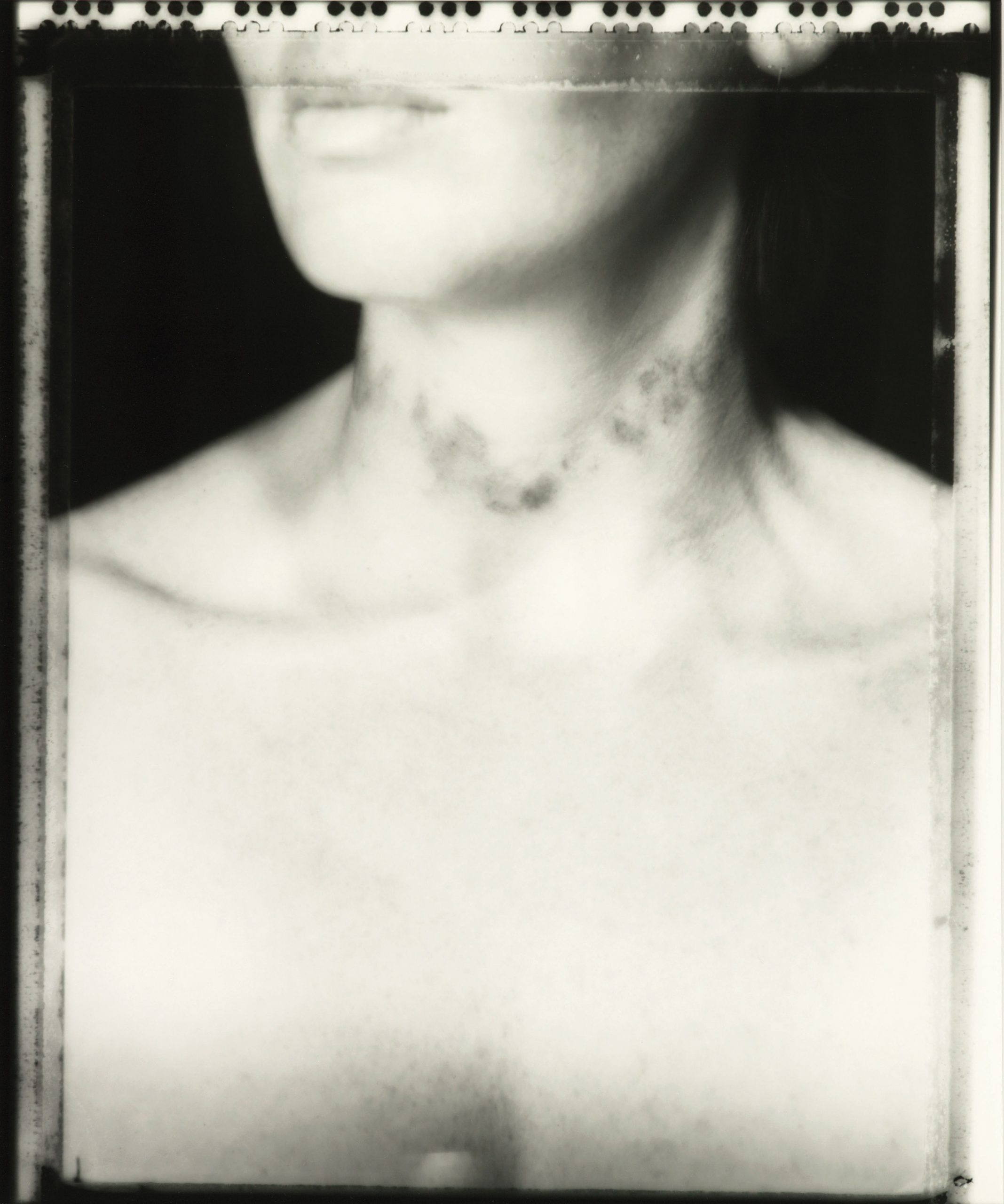

1. Roberta Thornley, Crying My Mother’s Tears (Meme), 2010. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. 2. Fiona Pardington, Choker, 1994. Collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

Protection

While trilling, the skylark ascended steeply and rested in space as if on some invisible platform. I decided to view the experience as a tohu mana or good omen.[6]

—Ngahiraka Mason

When writing for an exhibition catalogue, one seldom gets to preview the installation. At times, one does not even see the actual works, only reproductions. The upside is that juxtapositions can present themselves that might not otherwise be obvious. Scanning the object list for Autonomous Bodies, I find myself lingering on two photographs with quite different tones: Fiona Pardington’s Choker from 1994, and Roberta Thornley’s Crying My Mother’s Tears (Meme) from 2010. The images are compositionally similar. Both are bust length. Pardington’s eliminates the upper portion of the subject’s head, leaving her mouth, chin, and a chunk of ear visible. She is unidentified and unidentifiable, save perhaps to someone who knows her very well. Her neck is ringed with bruises, ostensibly from a strangulation. The context is unclear. Has she been subjected to violence or are the marks the result of an erotic game? One cannot know.

Crying My Mother’s Tears (Meme) is likewise marked by a measure of ambiguity. It portrays Thornley’s mother and was made after her youngest sister (one of five children, all female) left home.[7] I initially imagine that the title of the work refers to the artist’s own perspective; Thornley witnesses her mother crying and, being aware of the fact of the newly empty house, feels the sorrow herself. However, there is also a suggestion that Thornley’s mother is crying the tears of her mother, Meme, whose name is included in the title. The tears are fundamentally intergenerational, shared—both because family is a state of sharing, and because empathy is a common human trait.

Thornley’s mother is presented as physically as well as emotionally vulnerable. She is unclothed and unfiltered, marks of her age apparent. Her beauty is overwhelming, as powerful as her expression. The deep black background, the void space, recalls portraits of the Northern Renaissance by artists like Robert Campin (or so the theory goes) and Jan van Eyck. In such works, the subjects are depicted in great detail; the artists are at pains to describe every wrinkle, spot, idiosyncrasy. Idiosyncrasies define those we most adore. The portrait becomes a means of recording that which we know to be fleeting. A bruise will fade out, no matter what. A mother’s age will give way to her death. We do what we can to arrest the inevitable.

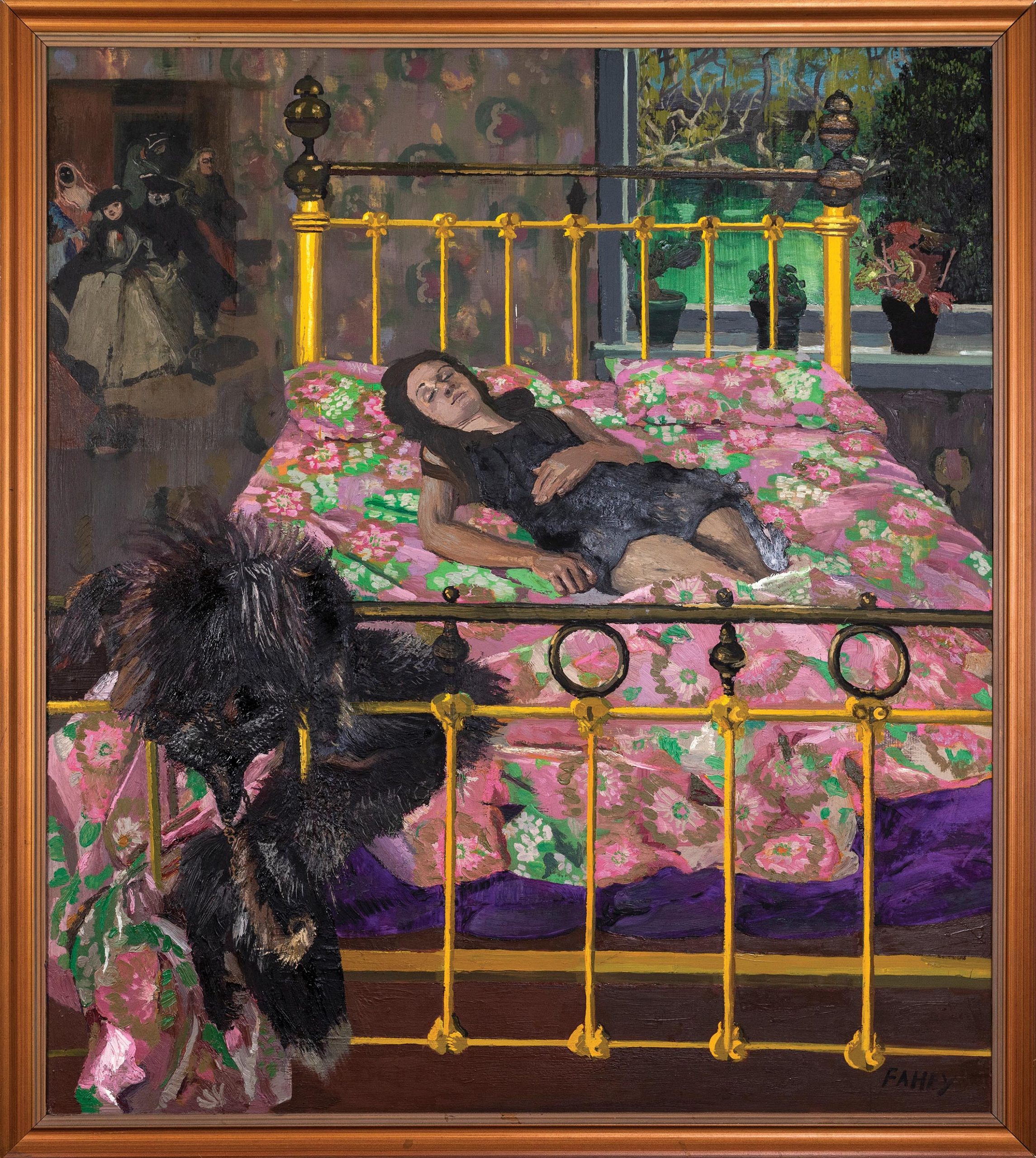

Jacqueline Fahey, Girl Dreams, 1978. Private collection.

A mother–daughter relationship quietly underlies Jacqueline Fahey’s Girl Dreams from 1978. The work shows one of her daughters, Alex, then about 17, sleeping on Fahey’s grand, comfortable-looking bed following a night out. A mid-18th century painting by Pietro Longhi is reproduced in the top left corner. It shows a masked man cosying up to a woman, and points to Fahey’s sense of the vulnerability of her adolescent daughter. The prominence of the bed again calls to my mind Olympia by Manet (Fahey quotes him directly in her Luncheon on the Grass of 1981–82). Girl Dreams might be an anti-Olympia. The young woman is differently self-possessed. She reclines as she does for her sake alone. The bed is a bulwark, not a platter. The implied spectator is a guardian (a notion reinforced by the titular ‘girl’), not a client. Agency can take the form of someone staring back at you. It can also take the form of someone blissfully dreaming.

Another work that suggests a space beyond the waking world is Hariata Ropata Tangahoe’s Anahera te pono (The faithful angel) from 2008. The eponymous angel kneels, wings spread, amid an array of gently illuminated pale pink clouds. Behind her is a heaven of hundreds and thousands paint strokes. Notwithstanding my agnosticism, I cannot shake the thought that they are souls or platforms waiting for souls to alight upon them. Anahera te pono has appeared in other works by Tangahoe. Her name recalls ngā Anahera Pono of the Rātana cosmology. The artist has described her as ‘a brown angel … trapped for almost all of her life by the Institution’.[8] Here, though, she is free. She has transcended the burdens of the earth, passing into another plane—where she is protected and, perhaps, protects.

Hariata Ropata Tangahoe, Anahera te pono (The faithful angel), 2008. City Art Collection, Wellington City Council.

Remembrance

… how earnest and sincerely concerned I was that the memories of women would not fade from the public sphere, nor their imagery![9]

—Allie Eagle

Autonomous Bodies is marked by the same subtle and complex thinking that I associate with artworks by Matchitt. Its animating impulses resist simple definition. As the title suggests, the show centres on questions of autonomy and physicality. The works are all figurative, but they are not necessarily portraits as conventionally understood, records of individuals. Matchitt describes the pieces she has selected as ‘experiential portraits’. Some are fictive. Some draw attention to politics, history, built or natural environments. Some look at private, small, or unglamourous moments that we might not always recognise as worthy of recording. The majority enfold shared experiences of the body, culture, gender, and sexuality, and testify to the fact that all of us exist within networks of peers, friends, and family.

Portraiture is associated with identity and remembrance. One of the key functions of a portrait is to memorialise the subject, to proclaim their importance, to get their existence on the record. Exhibitions often do something similar, providing snapshots of artists via their works, and arguing for their relevance. Autonomous Bodies goes further, asserting the value of both the particular practitioners represented and the diverse communities from which they stem. The show acknowledges the impacts of Western art history and settler colonialism, but it centres Aotearoa. European artists and cultures are positioned as peripheral. The local is autonomous, has reclaimed its autonomy.

Matchitt foregrounds artists who have risen to prominence since the 1970s, during a period of considerable and hard-won gains not only by women, but also by Māori, Moana, and LGBTQ+ people. Earlier Pākehā women who made figurative works—like Rita Angus, Louise Henderson, Frances Hodgkins, and Lois White—do not feature. The exhibition concentrates on living artists who emerged in their wake, and who reflect or helped to shape the increasingly plural society in which we live. There is a sense that appreciation of such artists is, rightly, growing (as I write this, Mata Aho Collective and Maureen Lander have just won the 2021 Walters Prize). A number of the artists in Autonomous Bodies—including Clark, Fahey, Ayesha Green, Tia Ranginui, Robin White, and the late Joanna Margaret Paul—have recently been, or will soon be, the subjects of significant shows. Kihara is the next representative of Aotearoa at the Venice Biennale.

At the same time, the exhibition alludes to the importance of maintaining and furthering recognition. As Matchitt notes in her essay, comprehensive touring shows dedicated to Henderson and Hodgkins have been staged of late. A large Angus exhibition will shortly open at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Few living artists receive such attention. Support of Māori artists can prove less solid than one might expect in this Māori land. Diane Prince has long been underappreciated. While Robyn Kahukiwa featured prominently in Nigel Borell’s Toi Tū Toi Ora (2020–21) at Toi o Tāmaki, she has not been accorded a retrospective by a similarly major gallery. Substantial solo exhibitions by living Māori artists are frequently found at smaller or more community-focussed institutions, like Māngere Arts Centre Ngā Tohu o Uenuku in Tāmaki Makaurau or Pātaka Art + Museum in Porirua. Centres of power can be slow to recalibrate.

For some, portraits—whether drawn, painted, photographic, or sculpted—are living embodiments of the people they portray. Even those of us who understand things differently might acknowledge the power of a picture to collapse time, or the illusion of the same. I tend to think of the collapse as applying to past and present, testifying to their consonance (we are not so different from our ancestors) and their inextricability (our ancestors endure within us). But the collapse can also involve the future. The effect of the present gasp of life is on the horizon. What we do now will have its impact. What we do not do, likewise. Our bodies will yield more bodies. Our collective portrait will find its place on the mantelpiece, or on the wall at the end of the hall. Autonomy is making the picture ourselves.

*

Essay commissioned by the New Zealand Portrait Gallery Te Pūkenga Whakaata for the catalogue for the exhibition Autonomous Bodies, curated by Gina Matchitt.

Autonomous Bodies

Curated by Gina Matchitt

26 August to 7 November 2021

New Zealand Portrait Gallery Te Pūkenga Whakaata

Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington

[1] Tusiata Avia, The Savage Coloniser Book (Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington Press, 2020), 77.

[2] Marian Evans, Bridie Lonie, and Tilly Lloyd, A Women’s Picture Book: 25 Women Artists of Aotearoa (New Zealand) (Wellington: GP Books, 1988), 236–38.

[3] Fiona Clark, ‘Guilty’, in Representing Trans, ed. Evan Hazenberg and Miriam Meyerhoff (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2017), 141. See also https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/discover-collections/read-watch-play/history/lgbtqi-histories-new-zealand-aotearoa/i-am-who-i-am.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 142.

[6] Ngahiraka Mason, Five Māori Painters (Auckland: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2014), 27.

[7] Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, ‘Crying My Mother’s Tears (Meme)’, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, accessed 1 July 2021, https://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/collection/2011-015/roberta-thornley/crying-my-mothers-tears-meme.

[8] City Gallery Wellington Te Whare Toi, ‘The Faithful Angel’, Scoop, 8 September 2000, https://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/CU0009/S00019/the-faithful-angel.htm.

[9] Felicity Milburn, Say Something!: Jacqueline Fahey (Christchurch: Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, 2017), 44.