When we describe a process, or make out an invoice, or photograph a tree, we create models; without them we would know nothing of reality and would be animals. Abstract pictures are fictive models, because they make visible a reality that we can neither see nor describe, but whose existence we can postulate.[1]

—Gerhard Richter

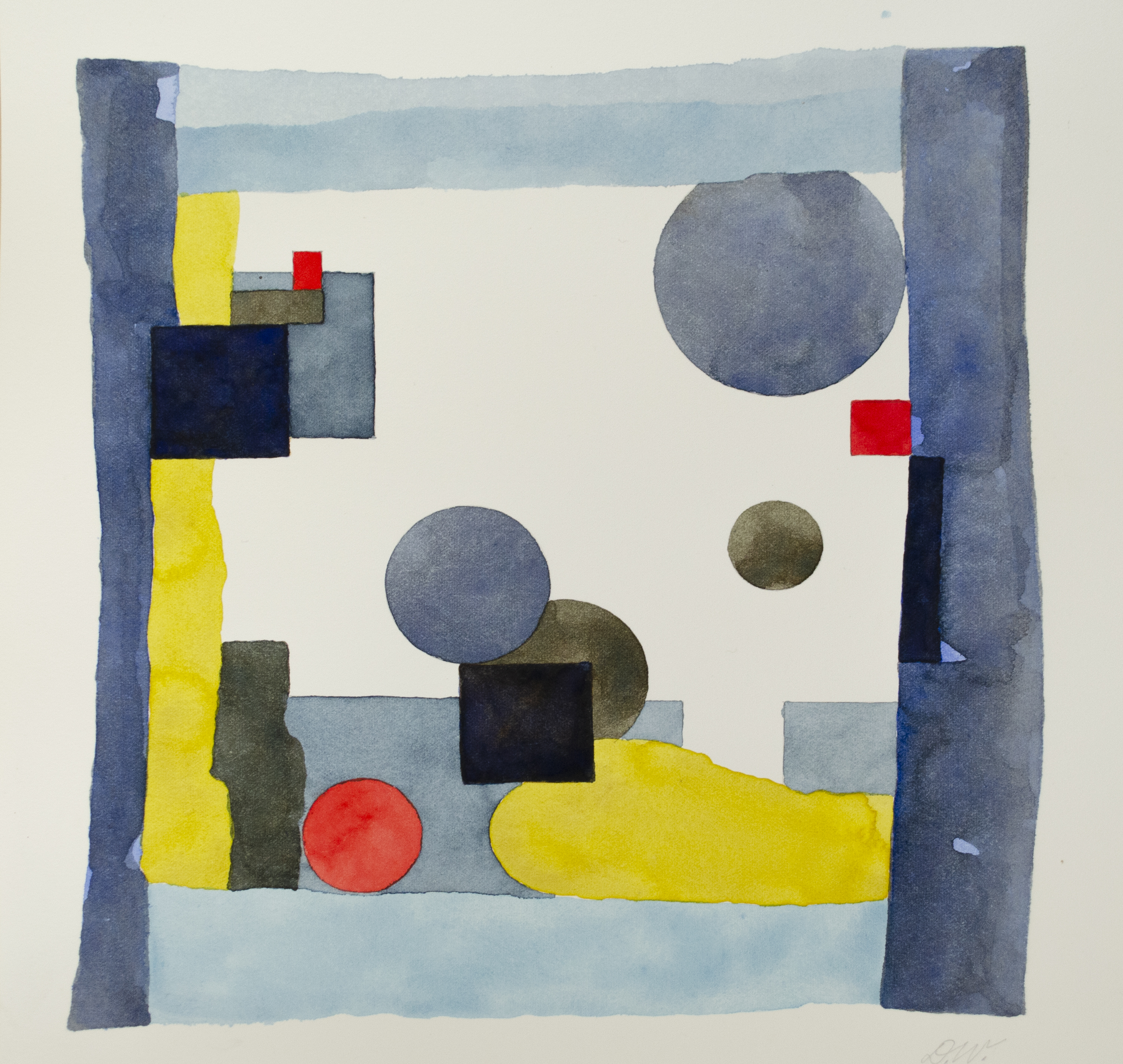

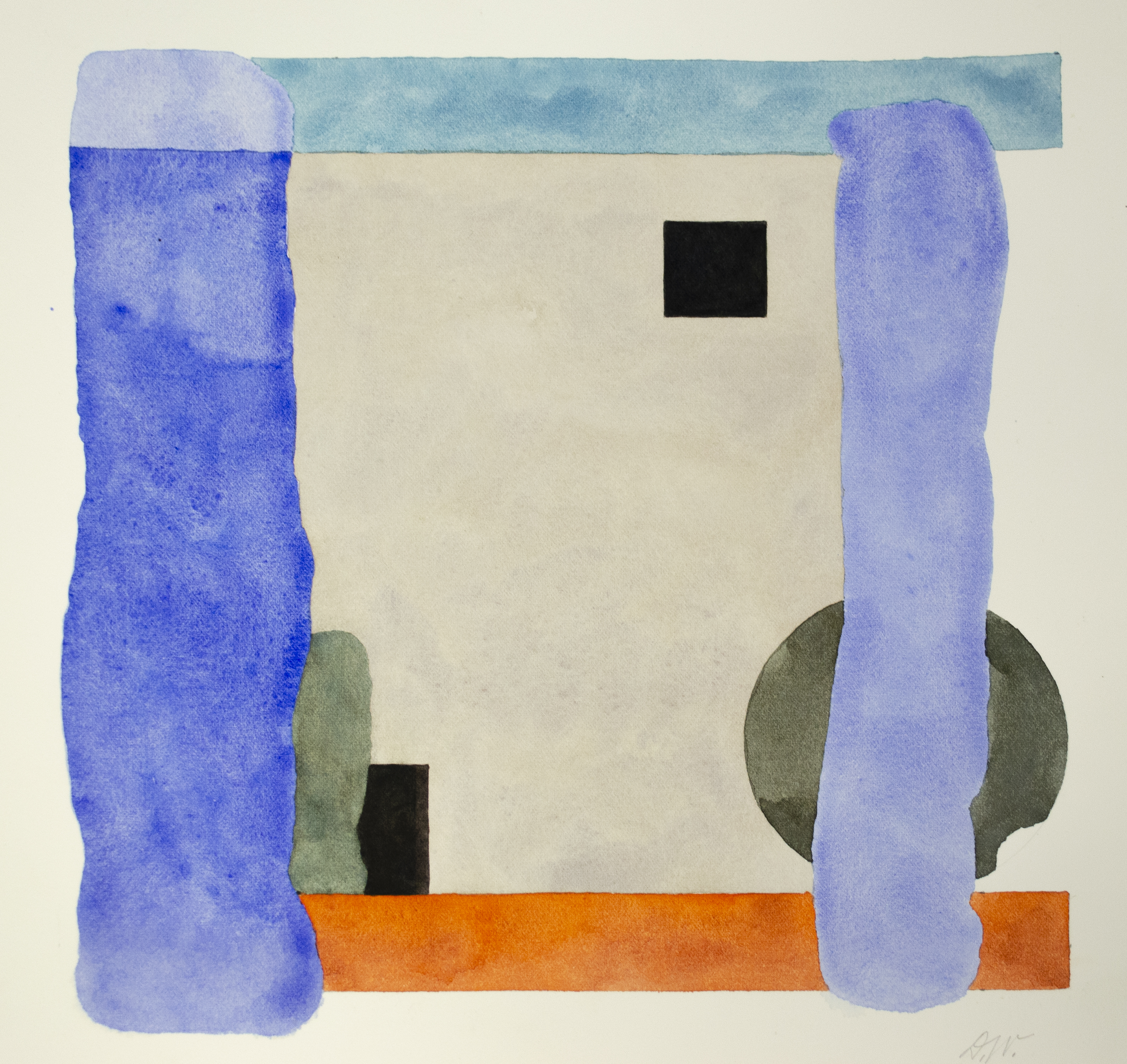

When presented with the pairing of Scarlett Cibilich and Denys Watkins, my initial impulse was to think of the artists as strongly separate, sharing a focus on painting but quite unlike one another in terms of approach and attitude. Watkins, who has been practising for some fifty years, tends to lean into painting as it is typically understood, using brushes to apply pigment (here watercolour or ink) to flat supports (here paper). To the parameters of the medium, he adds a limited formal vocabulary. Near-regular circles and squares are deployed alongside quivering bars and microbial rods in a sort of softened geometric abstraction that resonates with the work of painters of the early 20th century, like Sonia Delaunay and Sophie Taeuber-Arp. All are markedly hand-executed. The resulting pictorial constructions are broadly stable, self-contained, final.

Denys Watkins, Boom Box, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist and Millers O’Brien, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Cibilich, who is in the early stages of her career, actively tests the boundaries of painting. She works with myriad media: pen on graph paper, for instance; draped, digitally printed fabric; assemblages of aluminium tracking, dowelling, and strips of wood. Some works include elements typically associated with paintings, such as brushstrokes on board or cloth stretched over a wooden frame. But she is consistently interested in extending into other modes of production, whether those modes are close to painting (drawing, printing) or at something of a remove (clothing, industrial design). Cibilich’s works are deconstructive, breaking painting down into its component parts and investigating the extent to which those parts might still gesture towards the ‘tradition’. Her works tend to obfuscate the human hand. Her assemblages remain contingent, being reworked in response to their physical situation.

Scarlett Cibilich, The Line (installation view), 2019. Image courtesy of the artist and Millers O’Brien, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

However, the more I consider the work of Cibilich and Watkins, the more the characterisation of their practices as animated by distinct impulses feels like a story half told, even miscommunicated. While he certainly works within self-imposed limits, Watkins is in fact invested in a great deal of experimentation. His use of colour is particularly adventurous. He pings from a restrained, almost primary palette to one full of complex hues. He can do harmony, but is just as likely to plump for discord, to threaten pictorial rupture. He is not content to rest on compositional laurels, trying out asymmetry and symmetry both. Although he employs the device of a frame in multiple works, its form is unpredictable: now delicate, diaphanous, and on the point of drifting apart; now fat, lithic, and pressing inward.

Denys Watkins, Valeria, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist and Millers O’Brien, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Cibilich, meanwhile, seeks order within variety. In work after work, she returns to the straight line and the rectangle, whether sketching on the page or composing with bits on the wall. She reworks the same image file, producing fabrics that bear a common print. Nodding to modernist predecessors of her own, like Kazimir Malevich and Robert Ryman, she creates works that are all but monochromatic. She pins her sizing to a numerical constant, such as the metre (here, she echoes Marcel Duchamp and his 3 Standard Stoppages of 1913–14). In short, both Cibilich and Watkins establish strict frameworks within which considerable testing takes place. One might, of course, object that such a system is common to many artists, if not the majority. Indeed, ‘play with parameters’ might be understood to be a fundamental dimension of the development of an artistic voice (the unrestricted devolving into chatter).

Scarlett Cibilich, Fluid structures I, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist and Millers O’Brien, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Yet I continue to feel that there is a core sympathy between Cibilich and Watkins, one inadequately captured by the rambling category of painting or the subclass of geometric abstraction. Both seem to me to be engaged in a kindred project, seeking to produce works that in some measure transcend their makers, not merely cuing their status as carefully composed things, but instantiating an indefinite ‘rightness’ that is nevertheless recognisable upon arrival. Perhaps I sound as though I am positing something pseudo-spiritual: the painting as an incarnation of some divine template out there somewhere, the painter as Platonic demiurge. That’s not really my intention. I simply wish to suggest that these two painters are united in their pursuit of an evasive reality: an aesthetics, the contours of which they begin to trace by way of rigorous, methodical investigation.

*

Essay commissioned by Millers O’Brien to accompany the concurrent exhibitions The Line and SHUTTER BUG.

The Line and SHUTTER BUG

Scarlett Cibilich and Denys Watkins

6 to 29 June 2019

Millers O’Brien

Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington

[1] Dietmar Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 314. This much-cited quotation was originally included in the catalogue for documenta 7 (1982).