To look at Bushmiller as an architect is entirely appropriate, for Nancy is, in a sense, a blue-print for a comic strip. Walls, floors, rocks, trees, ice-cream cones, motion lines, midgets and principals are carefully positioned with no need for further embellishment. And they are laid out with one purpose in mind—to get the gag across. Minimalist? Formalist? Structuralist? Cartoonist![1]

—Mark Newgarden and Paul Karasik

Nancy’s Big Day Out develops out of two sorts of image of longstanding interest to Denys Watkins: the cartoon and the formal abstract. The influence of the former can be found in some of his earliest works. Studying in London in the 1960s, Watkins tended away from the cool formalism associated with Clement Greenberg and mid-century New York and towards a zanier kind of work, in sympathy with that of William T. Wiley, Patrick Caulfield, and members of Chicago’s Hairy Who group, such as Jim Nutt. He favoured cartoon-friendly techniques, specifically printmaking and watercolour (these were appealing for their ‘democratic’ affordability, as well as for the visual effects that they permitted). He collided the everyday and the fabulous, incorporating strange constructions or contraptions. He used comic-style black outlines and panels, giving the sense of a narrative, even when no particular narrative was discoverable. At the same time, he maintained an enthusiasm for rigorous design. All was precise and careful, nothing slapdash or haphazard. His works of the ’60s and ’70s are as tightly controlled as contemporaneous abstracts by the likes of Gordon Walters, though they are noticeably more down to earth (koru-like forms in Watkins’ Two Screws of 1975–76 grow hair).

Denys Watkins, Two Screws, 1975–76. Image courtesy of the artist and Webb’s, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

Denys Watkins, Yellow Dog, 2010. Image courtesy of the artist.

Cartooning and structure continue to mark recent works by Watkins. Some play up the comic book dimension, as is the case with Yellow Dog, a 2010 painting that centres on a plaintive Pluto. Others—like Meat Science of 2012, which features a rabbit holding a Wile E. Coyote-esque ‘help’ placard—subordinate it to a larger and largely abstract whole. Indeed, Watkins has for some years now emphasised abstraction. He populates his pictures with forms that slip between the geometric and the organic, resonating particularly strongly with works by artists of the early 20th century, such as Joan Miró and Sophie Taeuber-Arp. His use of composition, colour, and paint texture is uncommonly adventurous, while remaining taut, controlled. He has no typical or preferred solution to the problem of making an image that works. There are, however, recurrent motifs, which set up pictorial through-lines or rhythms. This is certainly true of the pieces in Nancy’s Big Day Out. On the surface of things, they are diverse in density, palette, and temperament. Yet there is a subtly consistent feature: a form (or series thereof) that nods towards the well-known comic strip character Nancy, created by Ernie Bushmiller in the early 1930s.

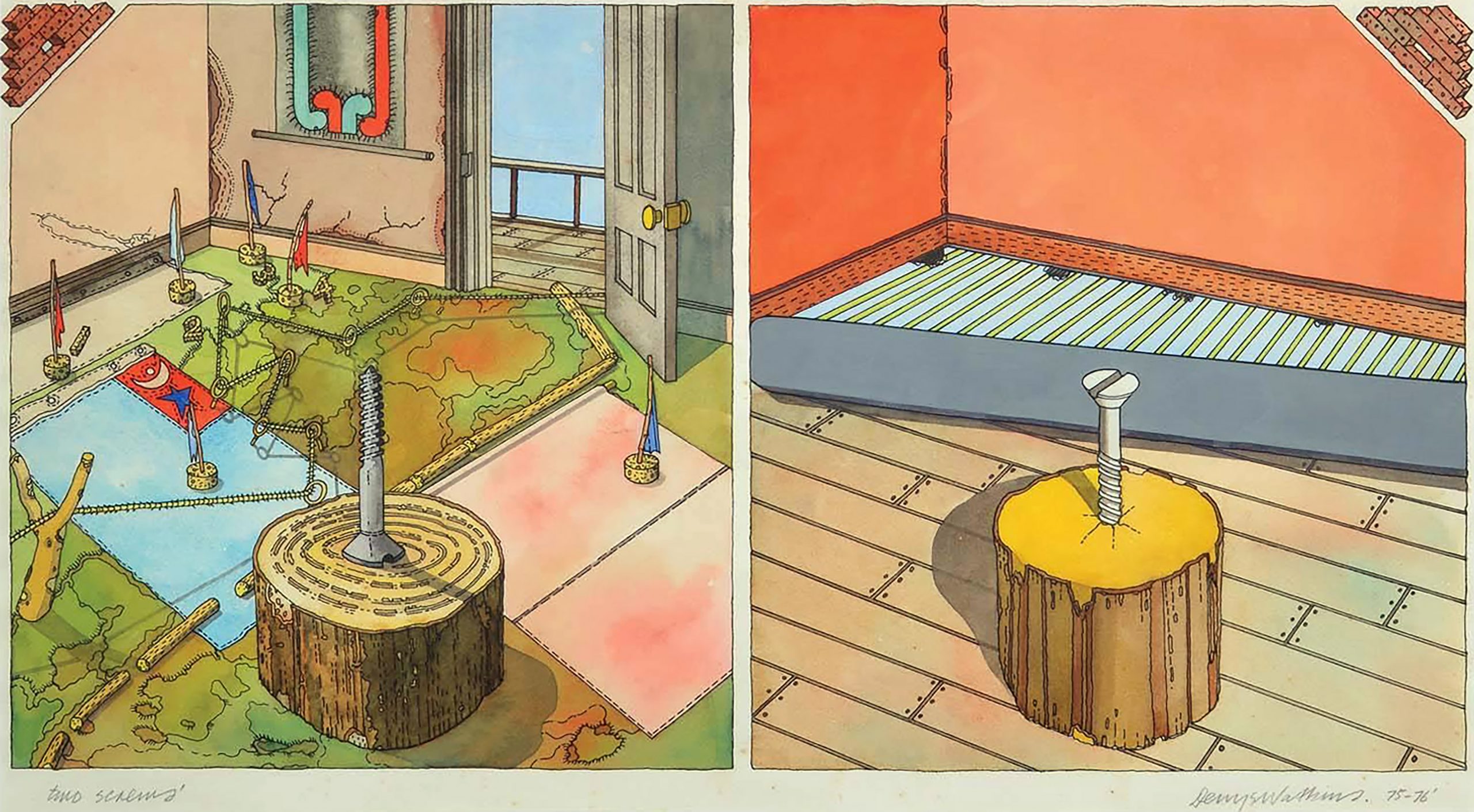

A Nancy cartoon.

Denys Watkins, Bessie, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist and Weasel Gallery, Kirikiriroa Hamilton.

Denys Watkins, HEATWAVE, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist and Weasel Gallery, Kirikiriroa Hamilton.

Watkins is attracted to Nancy in part as a consequence of her personality; she is strong-willed, typically outsmarting her male offsider, Sluggo. He also finds the design of the character compelling, being especially drawn to the form of her hair. She sports a dark bob that is bordered by nodules, the precise nature of which is unclear (are they meant to represent flyaways, perhaps, or curls?). Watkins has further abstracted the hairstyle and deployed it with great variety in the works in Nancy’s Big Day Out. It is sometimes outlined, sometimes solid, sometimes noduled, sometimes smooth, sometimes seen from the side, sometimes front on. It surfaces amid bacterial blobs, complex constructions, and fabric-like patterns. More often than not, it is quite unrecognisable, or rather it would be if one didn’t have Nancy as a reference point, didn’t know what to look for. As is frequently the case with Watkins’ pictures, there is a sense that he is playing with two interrelated impulses in those of us who see the works: our will to find balance and order, and our will to uncover a story. Where Bushmiller trades in explicit narratives, however, Watkins prefers ambiguity. The punchline is withheld. The gag never ends.

*

Text commissioned by Weasel Gallery to accompany the exhibition Nancy’s Big Day Out.

Nancy’s Big Day Out

Denys Watkins

28 October to 21 November 2020

Weasel Gallery

Kirikiriroa Hamilton

[1] Mark Newgarden and Paul Karasik, ‘How to Read Nancy’, in The Best of Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy, ed. Brian Walker (Wilton, CN: 1988), 98. The essay is also available online.