I looked at the natural world, and it seemed to share my feelings, to be trying in vain to escape its approaching doom. The waves of the sea sped in disorderly flight towards the horizon; the sea birds, the dolphins and flying fish, hurtled frenziedly through the air; the islands trembled and grew transparent, endeavouring to detach themselves, to rise as vapour and vanish in space.[1]

—Anna Kavan, Ice (1967)

They get inside you, Georgie Hill’s watercolours. They are uncommonly rich in their materiality, emphasising the sturdiness of paper and the vast range of effects possible working with a single medium and a small number of hues. Spend any amount of time considering them and they begin to infiltrate your experiences, colour your vision of the world about you. Complexly allusive, they flicker through diverse entities and phenomena. A flood of rainwater surging into a drain. The glassy tunnel of a rolling wave. The ragged luminosity of a damp sky. A stop light staining a steam-covered window. The streaky frills of a conch shell. The evocations differ from moment to moment and, no doubt, from person to person. They dart between categories, now biological, now elemental, now physical, now psychic, now earthly, now transcendent. The sense of energy is undeniable, but it is essentially elusive—as potent as sunlight and equally ungraspable.

The influences on Hill’s work are diverse. Literature has occupied a key position in her research of late. She is an avid reader of Anna Kavan and Doris Lessing, being impressed by the acuteness, experimental nature, and psychological depth of their writings. She is also attracted to their use of science fiction to posit alternate realities by turns plausible and fantastic, dystopian and more hopeful. Kavan’s 1967 novel Ice, which explores a world mired in conflict and on the brink of ecological collapse, has been a particular source of fascination. Storm-like gestures and spectrum-like gradations in Hill’s works resonate strongly with Kavan’s speculations and recall such real-world climatic catastrophes as the recent inundations in Germany and the heatwaves and wildfires presently ravaging Canada and the United States.

Georgie Hill, Prismatic Tectonics (installation view), Visions, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2021. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

Hill’s enthusiasm for Kavan and Lessing is closely associated with her longstanding interest in women who helped to advance the aesthetics and (often utopian) ideals of modernism, expanding conceptions of what art can be and do. She has looked at the lives and practices of artists and designers like Eileen Gray, Frances Hodgkins, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, being struck not only by the quality and transformative impact of their work, but also by their relative lack of visibility in historical accounts. Together with Kavan and Lessing, such individuals have become for Hill ‘a lineage of voices’, affecting her practice deeply, if not always overtly, and encouraging her to seek out further women whose contributions to the development of modernist art, and particularly abstraction, have been downplayed or overlooked.

For several years now, Hill has been examining ‘mediumistic’ artists, including Hilma af Klint, Madge Gill, Georgiana Houghton, and Emma Kunz. Af Klint has lately achieved widespread recognition for abstract works that predate those produced by the likes of Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian. She was a member of ‘The Five’, a group of spiritualist women from Sweden who were inspired by theosophical thinking (as, indeed, were Kandinsky and Mondrian) and engaged in séances.[2] Her visionary paintings incorporate elements that recall the natural world—no doubt reflecting an earlier interest in botanical art—and mathematical or scientific figures. Hill’s works, too, feature organic and diagrammatic components. Gestural passages encompass forms suggestive of petals, leaves, or fins. Curving lines, produced by slicing into the surface of the paper and exposing its white heart, can evoke contour lines on a map or isobars on a weather chart.

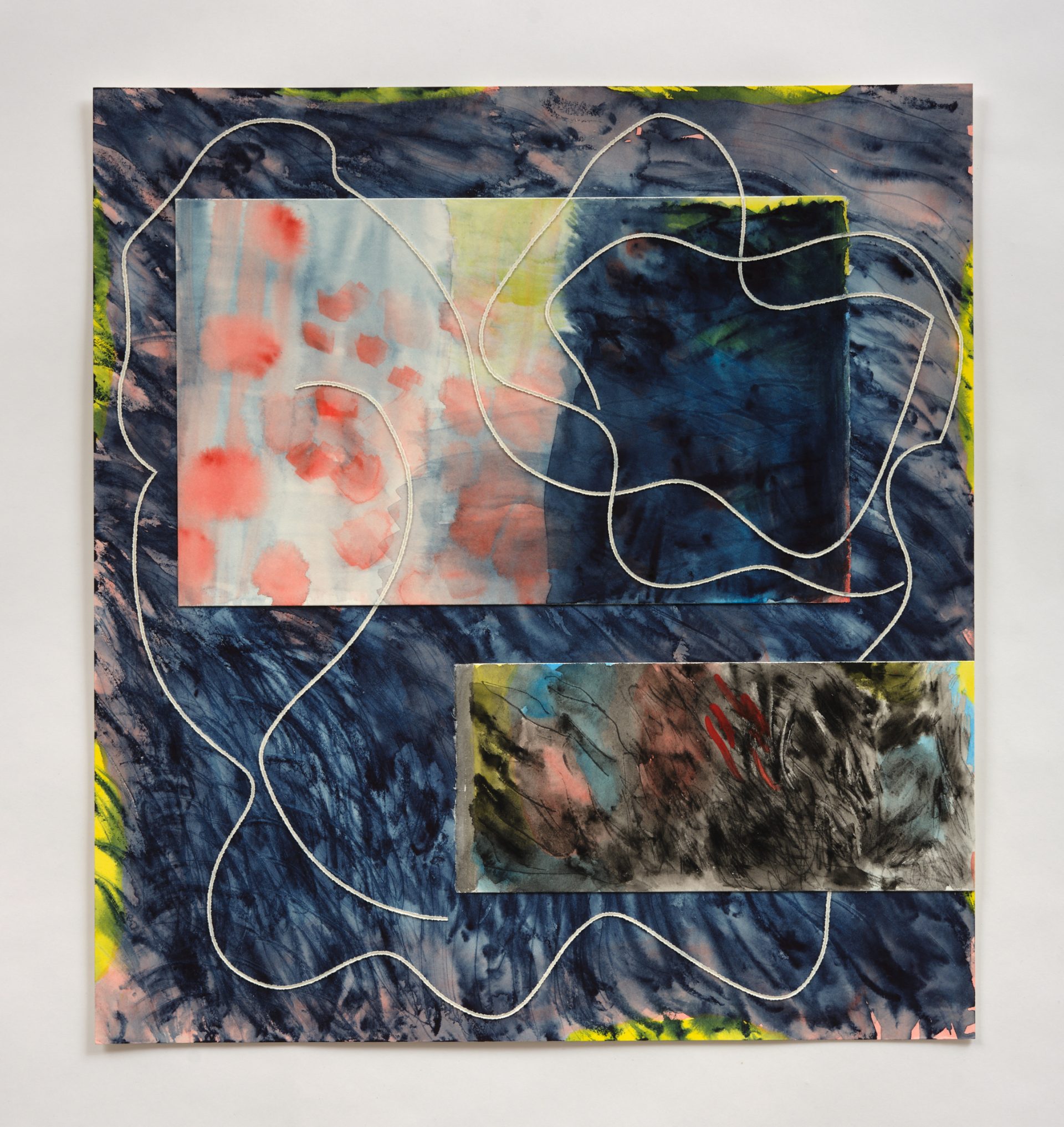

Georgie Hill, Prismatic Tectonics (4), 2021. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

Unlike af Klint, Hill is not driven by spirituality. Nevertheless, she remains interested in thought systems and world views beyond the Western scientific tradition, and in cross-culturally common values. As a maker, she increasingly favours intuition over calculation, embracing automatic processes consonant with surrealist practices. The gestural portions of her works are wholly improvised. The white lines are subject to some testing; Hill uses string to try out forms before fixing them. Incised and painted triangular grids found in earlier works are no longer in evidence. Collage elements in Prismatic Tectonics (3) and Prismatic Tectonics (4) echo the grids and their systematic colouration (the bands correspond to gestures in the base image), but the structures are sparser and more open. Although the lines are relatively thick, they are obviously superimposed rather than excavated. As such, they feel less permanent, more subject to change.

In other works, Hill has laid pieces cut from other gestural paintings over the base images. Prismatic Tectonics (1), Prismatic Tectonics (2), and Prismatic Tectonics (6) feature broadly quadrilateral fragments, which sit atop the supports in the manner of islands. In Prismatic Tectonics (5), perhaps the most radical work in the show, the pieces have been formed in such a way that they interlock, like puzzle pieces or tectonic plates. They neither subduct nor collide but float discretely over the just-visible mantle of the underlying painting. Hill’s works have often included beguiling illusionistic elements: cuts that mock string, designs that appear printed, fictive perforations. Here, a different sort of trick is at play. The crust does not form a coherent image, and it is not clear how many different paintings compose it. One strains to find a before in the after. The puzzle is irresistible and quite impossible to solve.

Georgie Hill, Prismatic Tectonics (6), 2021. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artistCourtesy of the artist.

There is a note of sombreness to Prismatic Tectonics as a whole. The titular allusion to geological forces tends to recall the truly natural disasters that sit alongside those created or exacerbated by humankind. As someone who experienced the Christchurch earthquakes first-hand, Hill is aware that existence is sufficiently precarious without our contributions. Manifold as it is, Prismatic Tectonics calls to mind the multiplicity of struggles we face as a fractured collective, and the difficulty associated with getting to the bottom of things. At the same time, it is hardly pessimistic. The works are far too animated for that, far too full of wonder. You write a postapocalyptic narrative to call for a course correction. You make paintings that speak to the cosmos, and to the diverse intelligences within it, because a call must be made many times and in many ways if it is to be answered.

Prismatic Tectonics

Georgie Hill

5 August to 4 September 2021

Visions

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

[1] Anna Kavan, Ice (London: Peter Owen, 2013), 134–35.

[2] Anya Ventura, ‘Secret Séances and High Masters: The Making of Mystic Painter Hilma af Klint’, Frieze, 11 October 2018, https://www.frieze.com/article/secret-seances-and-high-masters-making-mystic-painter-hilma-af-klint.