The Right Place?—Jhana Millers’ 2021 Auckland Art Fair presentation—features work by six early-career artists: Will Bennett, Harry Culy, Tyne Gordon, Ayesha Green, and Elisabeth Pointon of Aotearoa, and Lucy O’Doherty of Australia. The title of the show was a relatively late development. Millers’ initial intention was to focus on the dark sensibility of the ‘Antipodean Gothic’, an extension of the notion of the ‘New Zealand Gothic’, associated especially with Pākehā artists who rose to prominence in the 1990s, such as Tony de Lautour and the late Bill Hammond.[1] Culy has long declared his interest in the Antipodean Gothic, both as an aesthetic and as a means of evoking sensations of apprehension. Millers was struck by the extent to which other younger artists—including Bennett, Gordon, and O’Doherty—shared an interest in the sombre and unsettling, particularly as expressions of an awareness of the effects of settler colonialism and environmental degradation in Australasia.

The Right Place? (installation view), Jhana Millers stand, Auckland Art Fair, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, 24 to 27 February 2021. Image courtesy of the artists and Jhana Millers, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Such awareness is detectable in the work of Green and Pointon, artists of Māori and South Asian heritage respectively, as is a certain gothic quality. Green plays with colonial systems of knowledge and Victoriana with a fanciful edge. Pointon’s works often have a dark humour to them, and can suggest troubling situations, actual and potential. Ultimately, however, Millers felt that it was more meaningful to frame the interests of the selected artists more broadly, emphasising their diverse relationships with that old obsession in this part of the world: the physical-cultural environment in which we find ourselves. In 2021, Aotearoa is one of the few locations in which the staging of a conventional art fair can even be imagined. To the on-looking world, this appears the right place to be. But being conscious of hubris (the right place is only so at the right time), the range and extent of looming catastrophes, and—to paraphrase Allen Curnow—the stains of blood that write our stories, it seems only appropriate for Millers to append a question mark. Place is a given, but it can also be queried and changed.

*

Elisabeth Pointon (born 1992, lives in Te Whanganui-a-Tara) is dedicated to interrogating the status quo, placing a particular emphasis on systemic failures relating to marginalised communities. Her work typically centres on text, and is marked by wit and slipperiness of meaning. The artist adapts language and display methods associated with sales and showrooms (she has long worked for a luxury car dealership), finding richness within expressions and forms that might otherwise seem generic or vacuous. Her recent show at Jhana Millers, WHERE TO FROM HERE (2020), drew on personal and universal experiences. The central work, BIG TIME., an enormous blow-up version of the title phrase, alluded to a period marked by career successes (hitting the artistic ‘big time’) and private difficulties, as well as huge societal challenges—most notably the COVID-19 pandemic and the increased attention accorded to police brutality in the United States. Pointon asked whether calamities, produced by bad conduct and chance alike, might be turned into opportunities for reassessment and renewal.

Elisabeth Pointon, YOU HAVE COME TO THE RIGHT PLACE., 2021. Image courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Within The Right Place?, Pointon’s compact lightbox, YOU HAVE COME TO THE RIGHT PLACE. (2021), plays an outsized role. As is so often the case with her work, it possesses an ironical edge. In addition to appearing as part of the Jhana Millers booth, the artist features in the 2021 Projects Programme, Present Tense, curated by Michael Do. Her project is situated in Britomart, some distance from the Fair proper. For those seeking out that presentation, the booth is entirely the wrong place. On the other hand, of course, it is where you can buy a Pointon, so in terms of her interest in making a sale, it is indeed the place for the client to be. YOU HAVE COME TO THE RIGHT PLACE. is also significant in that it prompted the name for the overall Jhana Millers show. In extracting the phrase ‘the right place’ and adding the question mark, Millers herself has entered Pointon mode, wondering not only whether she’ll have the work for you, but also whether she has selected the correct stand. Is it sufficiently grand? Does it say ‘Jhana Millers’? How’s the location? Cash cow or white elephant? Visitors, remember, are not the only speculators at an art fair.

*

Over the past couple of years, the work of Will Bennett (born 1994, lives in Te Whanganui-a-Tara) has undergone a radical transformation. His earlier paintings show domestic spaces and small gatherings of people. They are marked by quotidian nostalgia, recalling snaps from old family photograph albums, but are also suffused with a haunting quality, suggesting small towns that are too quiet, tight communities that keep things that way. More recent works have seen Bennett intensify the sense of disquiet. Painted in lurid hues, they feature faceless figures with banners, shields, and swords, engaging in activities of uncertain purpose. The images resonate strongly with ‘speculative fiction’, synthesising fragments of the historical, the contemporary, and the purely imagined, and presenting worlds at once deeply weird and curiously plausible. The figures slip between the ancient and the futuristic, echoing now witches or religious fanatics as depicted by Francisco de Goya, now characters in a sci-fi film, roaming poisonous landscapes in protective gear.

Will Bennett, Floating through, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Bennett’s latest exhibition at Jhana Millers, Polyester Soldiers Stitch Witches (2020), related to his discovery of a Wellington group that engages in historical re-enactments concerning the Roman Empire. Studying his new works, I find myself drawing connections with other performance-based diversions, such as comic conventions, Renaissance fairs, and role-playing games. In the main, these are harmless, if not actively positive—convivial spaces that permit healthy escapism and the imagining of alternative realities. At the same time, Bennett’s paintings strike me as cautionary, warning against excessive enthusiasm for combat, for novel ritual, and for the promises of technological progress. They also evoke the dangers associated with romanticisation of the past, particularly by those of us who are white, for whom self-study all too easily becomes deluded self-celebration. It is interesting to note the consonance between Bennett’s images and those of figures involved in the recent storming of the United States Capitol. The barriers between fact and fantasy, history and myth, play and violence are slippery indeed.

*

The works of Tyne Gordon (born 1988, lives in Ōtautahi) centre on explorations of body and landscape, challenging our sense of being bounded units, separate from the world beyond us. Earlier paintings by the artist include ambiguous forms: curves at once hill- and knee-like, mounds by turns primordial and pubic. In more recent works, material is at the fore. Puddles and smears of paint suggest not only bodily secretions (blood, mucous, pus, sebum), but also chemical compounds—mineral deposits in thermal pools, perhaps, or the biproducts of mining activity. In addition to repulsive moments, the paintings possess great sensual appeal: surfaces you want to touch, even lick. There is other-worldliness. Environments are evoked that one cannot hope to roam. They might be storm-battered terrains still in the process of formation, out there somewhere in deep space, or aeons back in time—connected to us but necessarily unreachable, apprehensible only to the extent that they can be imagined. They might be places emptied of human life in an immediate sense, their surfaces toxic or in a process of detoxification.

Tyne Gordon, Visitant, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Gordon’s works also put me in mind of landscapes filtered through a pious or mystical sensibility. I think of the hauntingly abstracted spaces of Colin McCahon, which conjure the feeling of a yawning plain, the sound of a high-flung cataract. I think, too, of the Holy Lands as depicted in art of the early Renaissance, Italian and Northern: desert wildernesses conceived by Fra Angelico, the Golgotha of Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. Perhaps my tendency in these directions has something to do with the Christian propensity to hold death in the one hand and optimism in the other. Gordon’s works are steeped in decay, in the ‘abject’. They provoke an acute awareness of human frailty, as well as human physicality. And yet, since they are peppered with beauty and wonder, suffused with the sublime, I do not find them horrifying. Cosmic infinity makes personal finitude not merely tolerable, but enthralling.

*

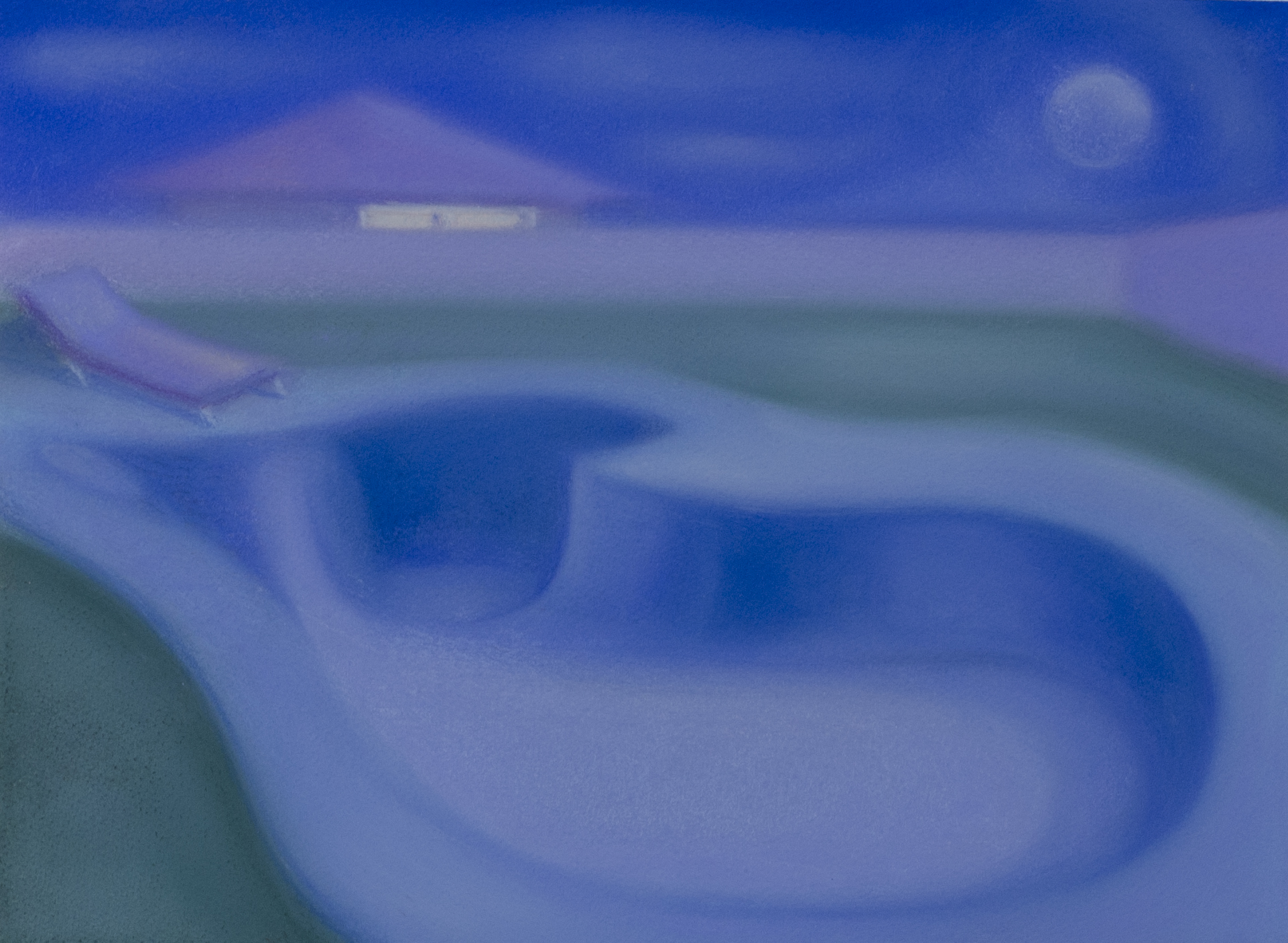

Lucy O’Doherty (born 1986, lives in Sydney) produces images so insistently lovely that they begin to feel unsettling. Whether she is depicting a heavily manicured urban backyard or an ‘untouched’ landscape, her treatment is equally painstaking. The composition is carefully worked out, gradations of colour smooth, paint and pastel strokes deliberately few. Her palette is ice-creamy. Edges tend to be blurred, as if the images are being viewed through a 1990s soap opera camera or eyes hazy with tears. Without exception, the scenes are empty of people and animals. Beaches gape. Diners are clientless. Swimming pools lie abandoned, often drained. At first blush, O’Doherty’s works can appear straightforward, even illustrative, but as one looks longer they tend to grow stranger, more whimsical, more difficult to interpret. What initially appears to be the trunk of a palm tree might in fact be the stand for an oversized umbrella. A form looming above a wall beyond a flamboyantly shaped pool might be an outdoor lamp, or a neighbour’s heater, or something else altogether.

Lucy O’Doherty, The moon searching for water, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

*

Harry Culy (born 1986, lives in Te Whanganui-a-Tara) has a particular interest in the complex relationships between people and places. He considers his artistic practice to be grounded in the tradition of documentary photography. Although he has on occasion worked in the studio, he more often turns his attention to the world as he finds it, seeking to capture rather than construct. His works typically centre on individuals and locations that are known to him and of personal importance. Following his return to Aotearoa from Australia several years ago, he photographed sites of childhood significance in the Hawke’s Bay. His practice since might be understood as an extended attempt to make sense of ‘home’. Many of his images show spaces heavily marked by human activity: industrial sites, treeless farmland, the worn corners of cities. They tend to be imbued with unease, a quality that connects with his longstanding interest in the Antipodean Gothic style in art, film, and literature, wherein haunting environments resonate with settler colonial violence towards indigenous people and the natural world alike.

Harry Culy, Untitled (best friends forever), Wellington, New Zealand, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Culy’s works in The Right Place? develop out of his recent exhibition at Jhana Millers, Mirror City(2020). The title reminds me of Janet Frame’s ‘mirror city’, at once a real metropolis and one of the imagination. More directly, it refers to Wellington, the city of mirrored buildings where the photographs were taken. Some works include literal reflections. Untitled (Devyn) (2019) shows a young woman standing in a bus shelter, the glass wall picking up the image of an adjacent picket fence, such that Devyn appears ghosted by the trace of a colonial dwelling. In Untitled (car window) (2020), entities inside the vehicle meld with others captured in the window. It becomes difficult to unpack the specifics; the photograph remains ambiguous. Ambiguity is important to Culy, echoing his uncertainty about the future, as well as the here and now. Looking at Untitled (best friends forever) (2020), I am acutely conscious of such uncertainty. The work shows a wall spray-painted with the phrase ‘best friends forever’. The scene is depopulated, the wall bordered with weeds, and I cannot help but think of the inverse of forever: impermanence.

*

Ayesha Green (Kāi Tahu and Ngāti Kahungunu; born 1987, lives in Tāmaki Makaurau) is best known for her cartoon-like paintings depicting the artist herself or members of her family. For some time now, she has incorporated botanical references into her works, being drawn to the diverse ways in which plants are used, named, and imbued with meaning. Her 2019 exhibition at Jhana Millers, Queen Elizabeth I, saw the artist create a large painting evocative of a florilegium, showing plants labelled in line with Linnean taxonomy. This contrasted with a collection of ceramic speech bubbles carved with the names of plants in te reo Māori (originally, of course, an oral language). A recent work, In the Extension of My Feet (2020), shows the artist in her underwear, with koromiko and poroporo seemingly sprouting from her feet. The painting recalls cross-culturally common narratives of metamorphosis, which are often used to explain the characteristics of plants, and which testify to the close relationship between humans, plants, and the earth upon which both depend.

Ayesha Green, Bouquet for Jameela #1, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Green’s latest series, Bouquet for Jameela (2021), sees her make use of a nineteenth-century guide to the meanings of flowers, The Sentiment of Flowers.[2] The book helped friends, lovers, and would-be lovers to communicate by way of blooms. A recent move from Ōtepoti to Tāmaki Makaurau separated the artist from her partner, and she has devised these works as painterly love letters, expressing aspects of her experiences with and feelings towards Jameela. Drawn from The Sentiment of Flowers, the plants depicted are all ‘introduced species’ in the context of Aotearoa. This state of affairs puts me in mind of Green’s monumental 2020 diptych, All of my lovers are immigrants (smooth my pillow). Each of the two panels shows the artist in bed with a different lover of non-Māori heritage. Each bed carries coverings with an earthy ground festooned with native flowers. Plants can be essential to and emblematic of the lands from which they spring. Yet they remain available for reinterpretation, renaming, transplanting. If the conditions necessary for flourishing are adequately accounted for, a plant can grow most any place you put it.

*

Essay commissioned by Jhana Millers to accompany the presentation The Right Place? at the 2021 Auckland Art Fair.

The Right Place?

Will Bennett, Harry Culy, Tyne Gordon, Ayesha Green, Lucy O’Doherty, and Elisabeth Pointon

24 to 27 February 2021

Jhana Millers stand

Auckland Art Fair

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

[1] For a concise discussion of the New Zealand Gothic in art, see Robert Leonard, ‘Hello Darkness: New Zealand Gothic’, Art and Australia 46, no. 1 (Spring 2008): 88–95, https://robertleonard.org/hello-darkness-new-zealand-gothic/.

[2] The book went through several editions. I have perused one from 1840. Robert Tyas, The Sentiment of Flowers: Or, Language of Flora (Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard, 1840).