Interesting what your parents say to you at the end. I said to my mother, ‘I’m probably not the type of son that you would have aspired to have,’ to which she replied, ‘I wouldn’t have wanted you any other way.’

—Paul Johns, 2021

BEEN HERE LONG? is the first solo exhibition by Paul Johns to be held in Tāmaki Makaurau in two decades. It represents a compact survey, spanning almost his entire career, from 1977—three years after he graduated with a Diploma of Fine Arts from the University of Canterbury’s School of Fine Arts at Ilam—to the present. Johns is recognised as an early exponent of conceptual and pop art in Aotearoa, and for his longstanding interest in gender and sexuality. His work is in sympathy with that of artists like Andy Warhol, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Billy Apple. While he is perhaps best known for his photography, Johns uses a wide range of media. BEEN HERE LONG? attests to this, including lens- and light-based works, paintings made by digital and manual processes, and a sculpture incorporating found objects. The styles and temperaments of the different works are similarly diverse. Some centre on text, some on image. Some are humorous, some more plaintive. But all touch on questions of intimacy and belonging, enfolding aspects of the artist’s personal experiences, while seeking to connect with anyone who might come upon them.

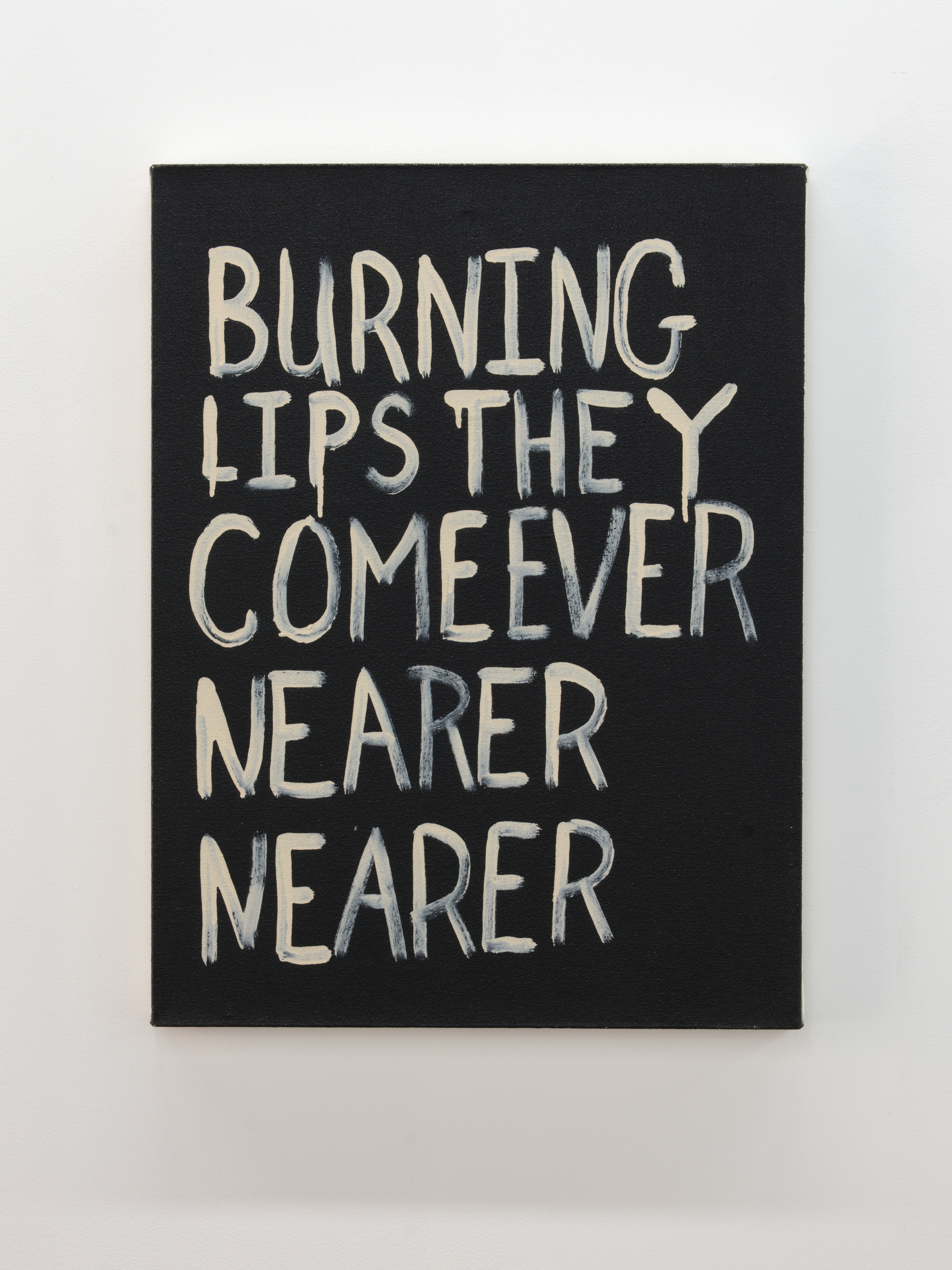

Hung just inside the gallery is Spell bound (1999), which reproduces a portion of a message sent to the artist. The words are hand-painted in block capitals, stacked, and without punctuation, such that they evoke—or perhaps become—a concrete poem: ‘BURNING / LIPS THEY / COME EVER / NEARER / NEARER’. Removed from its original context, the phrase achieves a level of ambiguity, openness to reimagining. But it’s also inescapably loaded. There’s no mistaking the feeling of ardent desire, which is shored up by the intense contrast between the black ground and the cream letters, and by the little bodily dribbles coming off the latter. Equally, there is a sense of frustration and pathos. This, too, is encoded in the words (‘nearer’ means not yet touching) and the physicality of the painting. Indeed, it is far from clear which element of the work, the formal or the textual, is doing the most work in terms of expression. I am reminded of Colin McCahon, who so confidently married the two (and often in black and white), and of poet and printer Alan Loney, who has written extensively on the significance of the form in which a text is issued.

Paul Johns, Spell bound, 1999. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

Text plays a similarly essential role in the show’s titular work, BEEN HERE LONG? (2020). This takes the form of a tall table, which is planted at the entrance to the show, tempting visitors into the space and calling attention to itself. Sandwiched between two sheets of clear acrylic are two speech bubbles picked out in neon. Each carries an utterance, one half of an exchange. Positioned under the bubbles are two rocks, the apparent interlocutors. One asks, ‘BEEN HERE LONG?’ The other replies, ‘A LITTLE WHILE’. Rock one, the questioner, was given to Johns when he was a young boy. It is from Mount Erebus, Antarctica, the site, years after it was collected, of Aotearoa’s most famous airplane disaster. Rock two, the respondent, was picked up by Johns at Peraki, Banks Peninsula. The bay has several important associations. It was the location of the first permanent Pākehā settlement in Te Waipounamu, a site of significant engagements between Māori and Pākehā, and a whaling station. Banks Peninsula more broadly was visited by the artist on numerous occasions during his childhood.

BEEN HERE LONG? the work nods towards a series of long-running interests on the part of Johns, including colonial histories, cross-cultural relationships, environmental degradation and animal welfare, and the process of grappling for a sense of belonging to the area of Aotearoa in which he grew up and has lived for most of his life. Like Spell bound, the piece is predicated on ambiguity. One might associate the Erebus rock with the New Zealand state and its claiming of the Ross Dependency, treating the object as a colonial entity, a displaced body, a recent arrival. One might associate the Peraki rock with the Māori presence in the area, ‘A LITTLE WHILE’ taking on a variety of subtextual shadows, including ‘long enough’ and ‘who wants to know?’ In any case, the stones appear personified, both as travellers, fundamentally mobile, and as beings characterised by ages and stages of development. Johns has commented that the Erebus rock is in all probability the geologically ‘younger’.

Paul Johns, BEEN HERE LONG?, 2020. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

In colliding the human and the geological, and raising the question of time, Johns might be understood to be highlighting the relative brevity of our individual lives and even of generations. I find myself focussing instead on the notion of the fundamental relatedness of the human and the non-human, regardless of tremendous differences in terms of animation and time scale. When push comes to shove, the stones and I are made of the same star stuff, just combined differently, baked for different periods. Then, too, there is a way of reading Johns’ sculpture that downplays the specifics of the componentry altogether, treating the rocks as placeholders that stand in for any number of individuals who might engage in a similar exchange. This is perhaps the more relevant approach in the context of BEEN HERE LONG? the show, which has been angled towards interpersonal relationships. Consider the form of the bar joke, in which ‘a man walks into a bar’. Two rocks are any two men. ‘BEEN HERE LONG?’ might reflect an appointment or be an opening line. ‘A LITTLE WHILE’ is a proposition accepted.

Bars and clubs have long influenced Johns and his practice. In his youth, they were important as spaces in which he was able to socialise with fellow homosexual men and other people who did not fit the mainstream. Such individuals soon became the subjects of works of art. The earliest pieces in BEEN HERE LONG?—two trios of images on 16mm movie film printed at large scale—depict a trans woman named Beverley Smith, whom Johns met and got to know via the party scene in Ōtautahi in the first years of the 1970s. His initial depictions of her, on film and in photographs, formed part of his Honours degree at Ilam, which involved the production of art works and a dissertation. Johns received a failing grade, and he was later told by one of the lecturers at the School of Fine Arts that this was a consequence of the perceived impropriety of the content rather than its quality. Sadly, Johns destroyed the dissertation (he is presently engaged in the process of reconstructing the text for eventual publication), but works made survive. Moreover, he continued recording his friends apace.

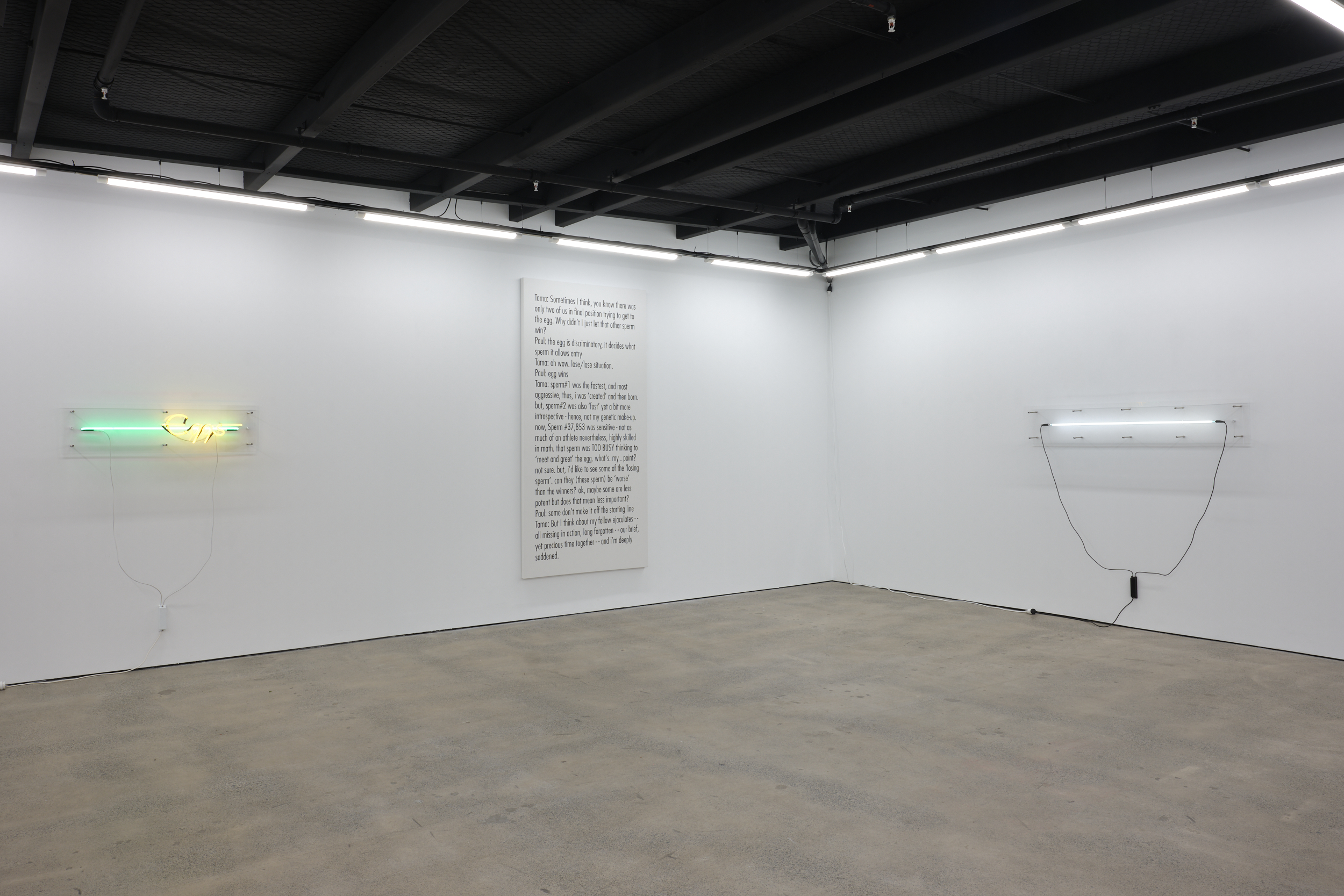

Paul Johns, BEEN HERE LONG? (installation view), Visions, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2021. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

The filmic images of Beverley in BEEN HERE LONG? were created in 1977 in Wellington, where she was living. She performed under the moniker Solitaire at The Balcony, a ‘nightclub and striptease parlour’ (as the National Library of New Zealand puts it) owned by the legendary Carmen Rupe, and named for a play by Jean Genet set in an upmarket brothel. Encountering Johns’ works, it might be tempting to dwell on the hostility to which Beverley and other trans women were subjected at the time. In addition to persecution, they faced the risk of prosecution. Until 1986, when the Homosexual Law Reform Act was passed by government, sex acts between men were illegal, and trans women were frequently confused for homosexual men. That many also engaged in sex work (likewise illegal) or exotic dancing (frowned upon) did not help matters. However, Johns does not dwell on experiences of suffering. While there is a noticeable sombreness to his images, Beverley is presented as self-possessed, strong. The visible edges of the film emphasise the cinematic dimension, suggesting grand narratives of which she is the star.

The four images of men in BEEN HERE LONG? are marked by a similar sense of self-confidence. Again, there is little jollity. Johns has no time for the fake smile, but neither does he have any interest in evoking victimhood. The works all possess a heightened intimacy. Three are Polaroids, and thus enjoy a degree of candidness and closeness by default. Sull’angolo tra Via Terenzio e Via Crescenzio (1985) shows the artist himself in a leather hat. The title refers to a location in Rome, not far from the Vatican. The other two Polaroids depict a man named Dan, who has since died. As with, Spell bound, the works draw on correspondence sent by the subject. The title of Auckland sucks (1998) conveys Dan’s attitude to the city, to which he had moved for a time. I was just saying it’s a shame no one made it fashion to have blokes in high heels (except to a degree in Glam-rock era). Anyway I think it would be good. (2001) is perhaps self-explanatory. The quotation appeals to Johns both because he himself embraced glam and punk rock, and because it alludes to the notion that relationships between dress and gender are culturally and historically contingent.

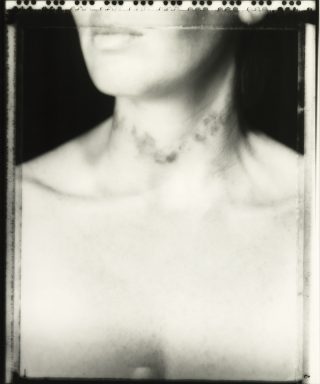

Paul Johns, I just thought I’d ring and say thanks, 1999. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

I just thought I’d ring and say thanks (1999), a large-format photograph in black and white, possesses an altogether different kind of intimacy. It shows a man in a rubber hood. In a sense, the work is the least personal, since the specific identity of the subject is minimally retrievable. But physical closeness is undoubtedly evoked. The headgear is strongly associated with fetish play. The rubber is dotted with liquid suggestive of sweat, while the overall form is not a little reminiscent of a condom-wrapped penis. The title of the work derives from a 1970 comedy, Myra Breckinridge, based on a novel by Gore Vidal, and famously concerned with gender and sex. In the film, the line is delivered by the outrageous Mae West. In the context of the photograph, it strikes me as newly amusing, partly because I tend to assume that the shrouded head is the speaker, and I thus imagine a muffled utterance, and partly because the delicateness of the phrase feels rather at odds with the intensity of the picture and the implied fucking. Then again, aren’t those of us who enjoy sex earnestly grateful when our particular appetites are satisfied?

Sex as generative moment, as well as pleasure bringer, underpins the final three works in BEEN HERE LONG? Although titled separately, Eggs (2021), #tamajanowitz (2020), and 200,000,000 (2020) essentially form a suite. Eggs is a neon composed of the eponymous word, in yolk yellow, superimposed over a green stripe. The work is, in a sense, a found object, having been given to the artist by his neon fabricator some time ago. Naturally enough, it embodies female gametes. The placement of the word ‘Eggs’ makes it seem to thrust to the right, towards the neighbouring #tamajanowitz, a UV-printed painting, which reproduces an extract from an online conversation between Johns and American writer Tama Janowitz (she is known, in part, for her association with Andy Warhol). To the right of the canvas, on a perpendicular wall, is 200,000,000, a bespoke neon that complements Eggs. The title reflects a perky human sperm count. Being white in colour, the work is visually in sympathy with the ejaculate to which it refers. The glow of both neons is suggestive of the force of life.

Paul Johns, BEEN HERE LONG? (installation view), Visions, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2021. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

The exchange between Janowitz and Johns is central to the suite of works. The text is rich, but two ideas within it stand out to me in particular: first, that any given conception involves an extraordinary number of failed candidate sperm; second, that the egg selects the winner. Janowitz expresses a sadness at this state of affairs, imagining other potential selves deemed unfit. But the suite overall seems to me to be more animated by wonder: wonder at the lottery-like odds involved in the production of each human life, wonder at the notion that there is a discretion at play, and wonder at that discretion being in a sense ‘female’, despite the enduring dominance of the male in so many other contexts. There is, I think, a certain comfort to be found as well, particularly for those of us who are not straight. We are as we are against all the odds, and perhaps by a kind of matrilineal assent. We own our place in the great multitude of generations that has unfolded amid the ferns and the rocks and the warm waters for a time we can scarcely comprehend. We’ve been here a while, and we belong.

BEEN HERE LONG?

Paul Johns

11 February to 20 March 2021

Visions

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

[1] See, for example, Alan Loney, The Books to Come (Buffalo, NY: Cuneiform Press, 2010). Like McCahon, Johns is interested in big questions. McCahon, of course, was wont to draw on biblical texts, tapping into the purported universality of the ‘word of God’. Johns’ approach here is different. He uses a particular text to get at a widely experienced sensation: longing.