Claudia Kogachi’s work leans into the personal. The artist frequently depicts herself and members of her family carrying out everyday and leisure activities, using these to explore interpersonal dynamics and emotional states. Early paintings show her and her mother engaging in competitive pursuits, such as boxing and table tennis, which become metaphors for the combative dimension of the parent–child relationship. The images are bold and cartoonish. The figures have blue skin, a reference to ‘feeling blue’ that also makes them appear otherworldly or like comic-book characters. Often, the scenes stretch credulity, not least when they take place in domestic settings that point to the circumstances of the underlying discord but are incongruous with the activities. It is not hard to imagine the pictures scribbled in a diary alongside entries about spats between mother and daughter. At the same time, the characterisations are frank and impartial. Neither figure is obviously presented as the hero or the villain. Neither is idealised. Their bodies are distorted, lumpy. The women are full of energy and strength, but they are not flawless.

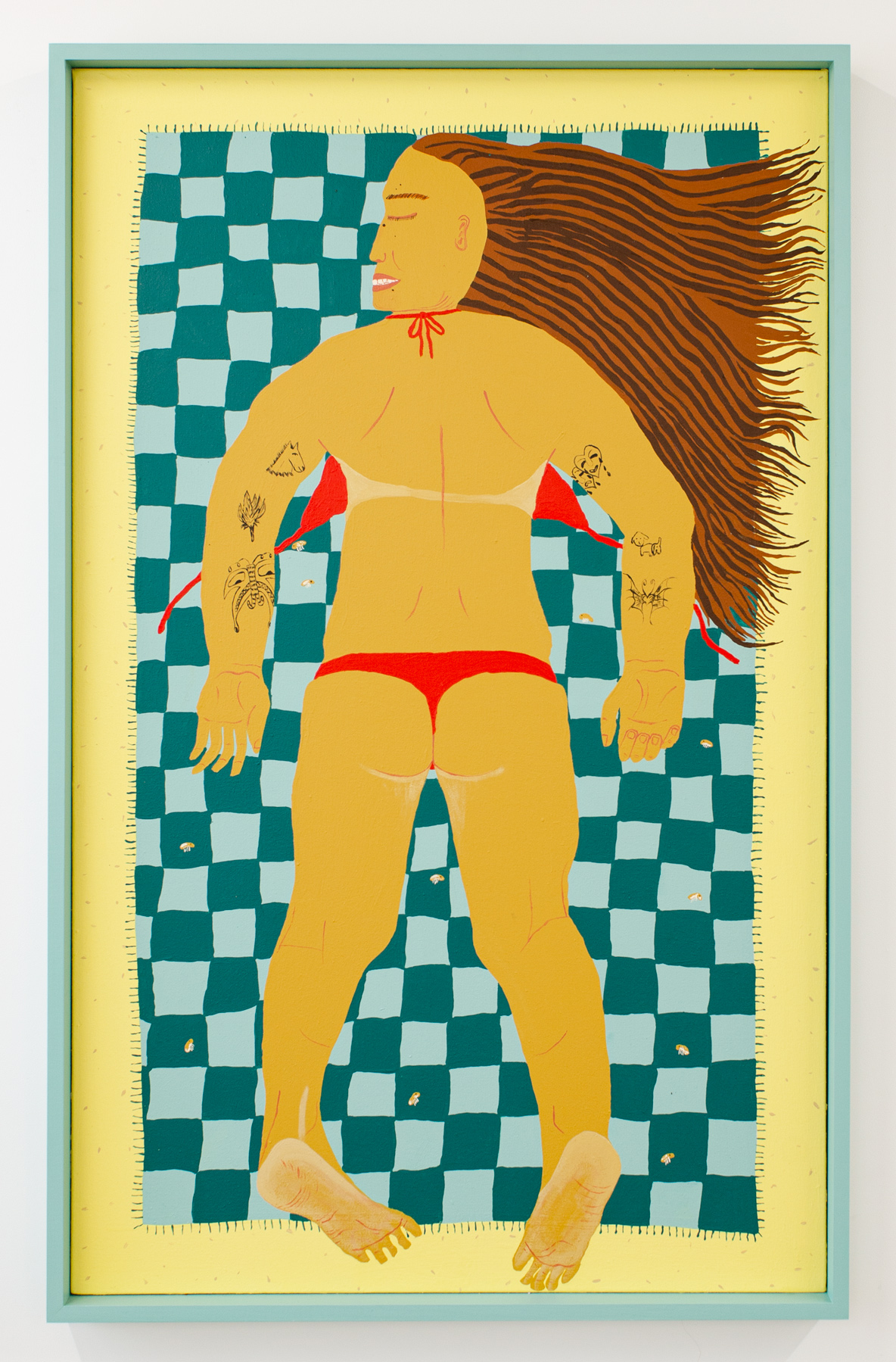

Claudia Kogachi, The one with the mosquitoes, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

Similar frankness is present in the seven paintings (all from 2021) that form the core of It Is What It Is. They show Kogachi and her partner being assaulted or impeded by a variety of creatures as they attempt to go about their business. In The one with the mosquitoes, the couple lies in bed. Jordi—who framed all the works in the exhibition—sleeps, but he has clearly been bitten by the eponymous insects. Kogachi is awake, her face a picture of anxiety. Both figures are presented in an unglamorous fashion, stressing their vulnerability. The scenes are more immediately credible than those in her earlier paintings. While few people box in the lounge, many are bugged by sand hoppers while sunbathing. As before, however, deeper narratives are at play. The artist speaks of anxieties and frustrations that she has experienced recently, in the context of individual relationships, and as a consequence of issues affecting broader communities, such as the local art scene. Kogachi keeps the precise irritants covert. But she amps up the intimacy in other ways. The works include personal features, like freckles and tattoos. The fantastical blue skin is gone.

Claudia Kogachi, The one with the mosquitoes, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

In 2020, Kogachi began producing pictorial rugs using tufting guns. The decision to do so was stimulated in large part by the nationwide COVID-19 lockdown, which limited her access to painting supplies. Three substantial bodies of work resulted, one reproducing items associated with her late jiichan (grandfather), one exploring jobs she could take on in order to support her art career, and one reflecting on memories of time spent with her obaachan (grandmother) in Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi. The last two series relate in large part to the pandemic, which caused Kogachi to worry whether she would be able to sustain her practice in a shifting world, and prevented her from travelling to visit her obaachan. Aspects of the rug works creep into her paintings in It Is What It Is. The one with the caterpillars, for instance, centres on a part-time gardening job undertaken by Kogachi to bring in extra funds. The one with the blue bottle jellyfish shows her practising surfing, a sport she has enjoyed for some time, and one that clearly connects with Hawaiʻi. One might detect in the bites and stings, and the frowns and grimaces, hangovers of a year of serious stress.

Claudia Kogachi, The one with the blue bottle jellyfish, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.

However, as has long been the case with Kogachi’s work, there is also an air of hopefulness and stability. The images abound with delightful and humorous details. They possess great pictorial strength, being marked by balanced compositions and melodic patterns. In The one with the head lice, for example, the artist’s hair forms a bold design. Painted in bands of brown, it spreads out to the edges of the image. At first glance, the work might appear to be an aerial view of a landscape. In a sense that is appropriate. For the nits colonising her crown, she is a terrain. Her face is peppered with delicate creases, but it remains placid. Possibly she is snoozing, as yet unaware of the invaders. Possibly she is blocking them out. I recall Kogachi’s choice of title: It Is What It Is. As New York Times columnist William Safire has pointed out, the applications of the phrase are many. It is both an expression of philosophical resignation and an avowal that one refuses to dwell on a lousy situation. Bad things happen. They bother one, keep one awake at night. But one deals with things, and moves on. Ultimately, Kogachi’s works represent a spectacular catharsis.

*

Claudia Kogachi was born in Awaji-shima, Japan, in 1995. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts. In 2019, she won the New Zealand Painting and Printmaking Award. Recent exhibitions include: New Artists Show 2020, Artspace Aotearoa, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland; Obaachan during the lockdown, Wahiawā, Hawaiʻi, Te Tuhi, Tāmaki Makaurau; Uncle Gagi, play_station, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington; and Everyone Has a Horse Phase, Sanderson Contemporary, Tāmaki Makaurau (all 2020).

*

Essay commissioned by Jhana Millers to accompany the exhibition It Is What It Is.

It Is What It Is

Claudia Kogachi

26 March to 10 April 2021

Jhana Millers

Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington