The kauri surrounding Otitori Bay Road in Titirangi stand near the edge of Te Wao Nui a Tiriwa, the Waitākere forest, on which Te Kawerau ā Maki placed a protective rāhui in late 2017. Many of the trees are afflicted by the disease known as ‘kauri dieback’. Their golden leaves fall on the paths that lead down from the roadside to McCahon House, the dwelling inhabited by Colin McCahon and his family after they moved to Tāmaki Makaurau in 1953, and Parehuia, the purpose-built house and studio occupied by each McCahon House Artist in Residence. From February to April this year, the position was held by one of Aotearoa’s most highly respected living artists, Emily Karaka.

The residency has been of great meaning to Karaka, who knew McCahon. In 1979, he attended her first solo exhibition, held at Outreach in Ponsonby, and bought a drawing representing a bush path. Speaking with her at the opening, he offered words of encouragement, maintaining that she would go far. About the same time, Karaka had an unusually potent dream, her first in vivid colour. She recently wrote of it, ‘I was being chased but just as I was about to be caught a large bright lime green island emerged with a stone plinth in the middle of it. I suddenly penetrated the rock; I wasn’t caught.’[1] When she awoke, she felt pregnant—although she was not—and found herself caressing stones.

Perplexed by the experience, Karaka turned to McCahon for counsel. He admonished her to keep the dream to herself and cautioned her that people would ‘throw stones’. The warning proved prescient. For many years, Karaka has been an iwi representative as well as an artist, and, in both capacities, she has attracted hostile reactions. She has always understood her responsibilities to be enmeshed. She states that ‘politics is life is art is life is politics. It’s all interwoven, like a whāriki, like a mat.’ Nonetheless, her time at Parehuia has given her a renewed sense that it is possible and important for her to concentrate on her art at this stage in her life.

Emily Karaka at Parehuia, 2021. Photograph by Sam Hartnett.

The residency is further significant to Karaka because Parehuia lies in the rohe of Te Kawerau ā Maki, one of her iwi. She is the first person from the iwi to be a McCahon House Artist in Residence. The name Parehuia was bestowed by the late kaumātua Eru Thompson in 2009, and it refers to a revered tupuna of Te Kawerau ā Maki. At the recent Gate Dinner IX, a celebration of Karaka’s tenure, hāngī master Rewi Spraggon commented that the name was highly appropriate for a whare who, mother-like, embraces and protects many artists and families. He noted, too, that it was fitting that Karaka was the first Kawerau ā Maki artist to hold the residency, since she, like her ancestor, Parehuia, is a wahine rangatira.

While living and working in Titirangi, Karaka was watched over not only by McCahon, whom she considers a grandfather figure (she observes that he even looks a bit like her koro), and her tupuna, Parehuia, but also by the atua kauri of Te Wao Nui a Tiriwa. They are important as ancestors of the deep past and as entities that have supported Māori for generations: creating shelter, harbouring food, and providing wood for waka and kāpia, gum, used in tā moko. Spending days in the presence of the trees at Otitori Bay Road, Karaka grew increasingly aware of and affected by the spectre of the kauri dieback sickness from which they are suffering. McCahon famously painted the thriving trees he saw. Karaka was summoned to respond in her own way to the kauri and their current predicament.

In February, Tāmaki Makaurau was ordered into lockdown due to an outbreak of the Coronavirus. Karaka reflected on the fundamental connection between the dieback and the pandemic, understanding them to be expressions of a natural world that is ailing and that demands a concerted response from human beings. Rāhui the exhibition draws parallels between the diseases and between core measures taken to counteract them, particularly the lockdowns used to curb the spread of the virus, which are themselves sometimes referred to as ‘rāhui’, and the Kawerau ā Maki rāhui that safeguards a large portion of Te Wao Nui a Tiriwa, prohibiting people from entering the forest, and thus preventing them from tracking the infectant about.

Emily Karaka, Te Wao Nui a Tiriwa; Kauri Can’t Breathe, 2021. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

Both approaches involve limiting human movement, and both require widespread compliance to succeed. If individuals choose to ignore the lockdowns and the rāhui, they will not work. Cooperation is vital. Karaka also alludes to differences between the responses. Paintings like Te Wao Nui a Tiriwa; Kauri Can’t Breathe acknowledge the Waitākere Ranges Heritage Area (WRHA) Act 2008, an Act of Parliament aimed at promoting the wellbeing of the Area. The Act was used by Te Kawerau ā Maki as legislative support for the rāhui. Following some campaigning, the protection was endorsed by Auckland Council. The situation is therefore one in which mana whenua have been leaders, serving as essential kaitiaki in conformity with their rights.

While official responses to the Coronavirus pandemic have not overlooked Māori entirely, they cannot be said to have accorded iwi an especially prominent role. By drawing attention to the WRHA Act 2008, Karaka indicates that governing bodies stand to benefit from more meaningful engagement with iwi and with mātauranga Māori. This notion is underscored in Rāhui; Mana Motuhake, which includes the expression ‘mana motuhake’ and the tino rangatiratanga flag. Karaka comments that the rāhui embodies autonomy or self-determination. It also promotes the wellbeing of all who live in the wider Tāmaki Makaurau area, since Te Wao Nui a Tiriwa is the lungs of the isthmus. In designating the forest tapu, and limiting access, mana whenua maintain the mauri of kauri, land, and people.

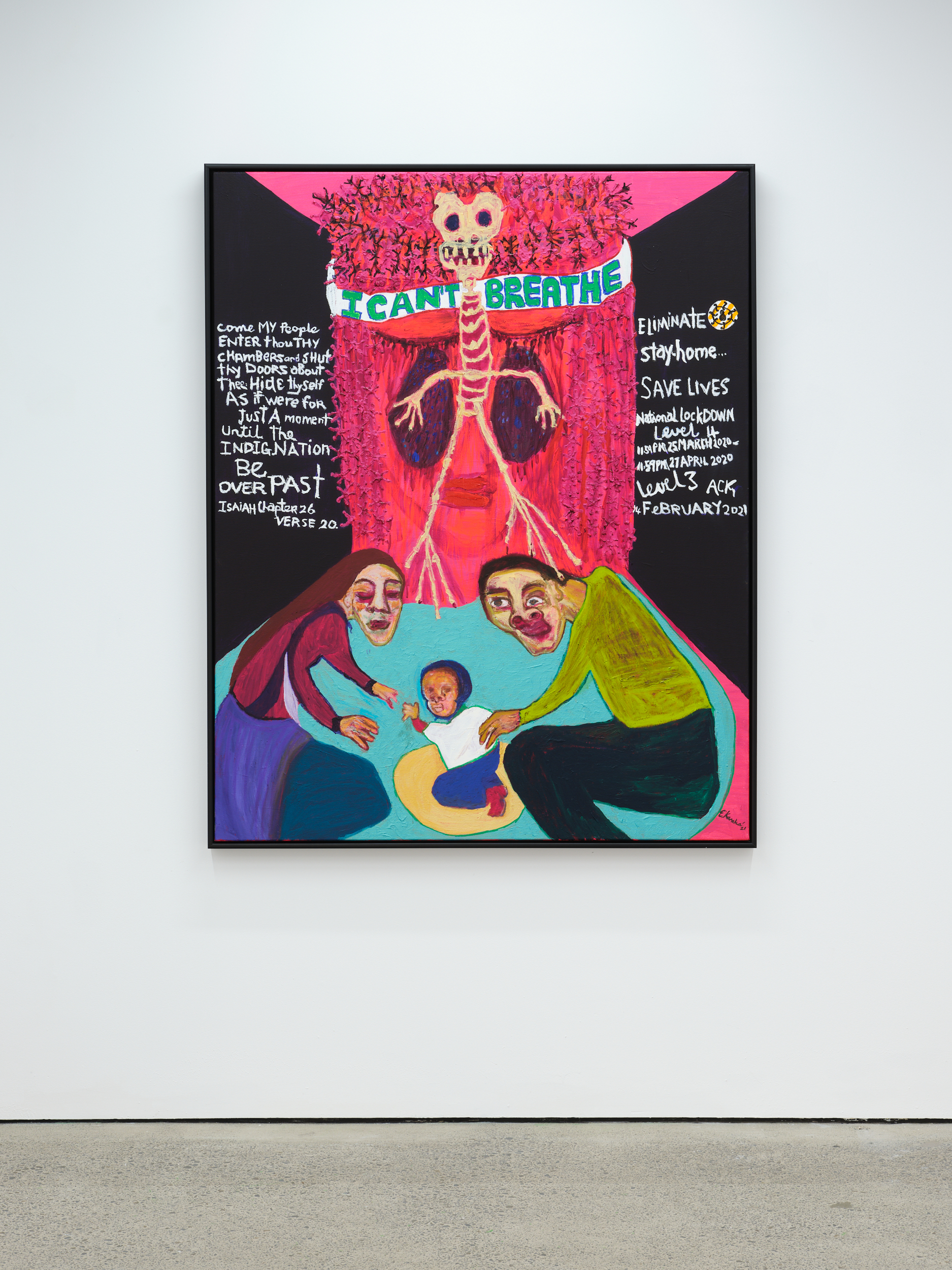

I Can’t Breathe, which features cartoon-like figures quite unusual within Karaka’s practice, is inscribed with Isaiah 26:20 from the Old Testament: ‘Come, my people, enter thou into thy chambers, and shut thy doors about thee: hide thyself as it were for a little moment, until the indignation be overpast.’ The passage primarily ties into the notion of lockdowns. However, one might also draw a connection with other attempts to conceal or shelter oneself. It is worth noting that ‘I can’t breathe’ is a phrase closely associated with the Black Lives Matter movement, having been uttered by numerous black people assaulted or murdered by police.[2] A lockdown is but one form of protective hiding; a pandemic is but one form of widespread disease.

Emily Karaka, I Can’t Breathe, 2021. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

The presence of a biblical passage—and particularly one rendered in white over a dark ground—naturally recalls McCahon, who made extensive use of similar texts. The detail is perhaps the clearest acknowledgment of McCahon in Rāhui, beyond the emphasis on the ngahere that he lived in and painted. Karaka observes that she is inspired by McCahon’s dedication as an artist as much as by specific works that he produced. In a broad sense, their practices are in sympathy. Paintings by both reflect on place and spirituality, incorporate words, and are marked by emotional intensity. McCahon was deeply interested in te ao Māori. Karaka inhabits that space, exploring matters that he was not able to explore.

Rāhui is imbued with pathos. A monumental work on paper, Pandemic, is perhaps the most directly mournful of the pieces. It centres on an elliptical form, which evokes at once a microbe, an eye, a bowl, a basket, and an area cordoned off. The structure is filled with mask-wearing human bodies, trees, and waka. Dominated by painful red, the picture powerfully suggests the kindred nature of the atua kauri and the descendant people, both suffering together. A second large work on paper, Titiro, is rather more optimistic. It includes a similar ring form, which, Karaka notes, recalls a submarine and its periscope. Three masked people, two with moko on their exposed upper bodies, look out of the portal. Next to them is a group of kauri. The space beyond the figures and trees glows neon orange, more sunset than wound, a blazing life force.

Emily Karaka, Pandemic, 2021. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

3 of the Team of 5 Million; Do Not Enter, which is painted on a pair of conjoined canvases, lies somewhere between Pandemic and Titiro. A whānau of three is shown, the members in everyday clothing. The two parents seem at ease, while the child looks upward, mouth open. A skeletal figure straddles the black bubble that surrounds them. Behind them and to the side is a forest of dark, naked trees, outlined in blood red. A pou stands at the centre of the work, evoking both a pou whenua, used to signal that an area is under the rightful jurisdiction of those who have placed it, and a pou rāhui, used to signal that an area is tapu and that entry is prohibited.

A triptych, composed of paintings on unstretched canvas, shares the title of the show, Rāhui. The central painting depicts a cluster of kauri, all ostensibly in good health, against an ultramarine ground. The flanking pieces embody the concept of rāhui, each focusing on figures that embrace so closely that they seem to meld into one. Golden leaves that have fallen from the kauri around Parehuia and McCahon House form cloaks for the figures. Karaka refers to the leaves as the roimata, the tears, of the trees. There is a sense of sorrow, but the figures have a protective aspect too. One imagines kauri nestled within the body-cocoons, their mauri being safeguarded by the kaitiaki.

Fallen leaves also form cloaks in Rāhui; Mana Motuhake. Like 3 of the Team of 5 Million; Do Not Enter, the painting shows a group of people alongside kauri under rāhui. Although outlined in similar red, the trees appear to be healthier, since they are green and carry leaves. The whānau stand in the land with the kauri and the pou rāhui. They are directly acting as guardians, not entering the zone marked off as tapu, of course, but watching over it. They take care of the kauri just as the kauri have so long taken care of them. There is symbiosis and there is reciprocity. Health comes from working together, with our peers human and otherwise.

Emily Karaka, Rāhui (installation view), Visions, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2021. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

The last four paintings made at Parehuia are grand and sombre. Each is six feet square and so corresponds roughly to the size of a person with arms outstretched, as if to embrace a mighty trunk. With their black grounds and oil pastel smears, the works faintly recall chalk boards. Rāhui at Taurarua; Kaitiaki at Mataharehare is something of an outlier. It relates to a rāhui at Dove-Myer Robinson Park in Taurarua, or Judges Bay, Parnell. This is aimed at preventing the construction of a memorial to New Zealand’s ‘worst civil disaster’, the 1979 plane crash at Mount Erebus, Antarctica. Taurarua has its own deep history.[3] It was once home to a Waiohua pā, which was attacked by Ngāti Whātua as part of a broader conflict. Later, it was occupied by Pākehā ‘early settlers’, such as John Logan Campbell. A mass of headland was cut away in the early 20th century.

It has long been claimed, including in official records, that Te Waiohua were destroyed.[4] However, descendants today make up the Waiohua-Tāmaki Rōpū, which comprises Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki, Ngāti Tamaoho, Ngāti Te Ata, Te Ākitai Waiohua, and Te Kawerau ā Maki. Karaka’s painting testifies to the ongoing relationship between Te Waiohua and the Taurarua area. Central to the work is a spectral white pōhutukawa, which refers to a large tree near the site of the proposed memorial. The artist points out that pōhutukawa, like kauri, are vulnerable to disease, being plagued by ‘myrtle rust’. The white of the tree evokes its spirit and acknowledges the ancestral presences and stories that too often are elided to allow the progression of colonialist agendas.

Kawerau ā Maki Rāhui; WRHA Act 2008 gives particular prominence to the eponymous Act. Using text, Karaka highlights the immensity of the Waitākere Ranges Heritage Area, as well as the fact that it subsumes both private and public land. She reproduces the preamble to the Act, taken from a speech made by Te Waatarauihi at the Kohimarama Conference of 1860. The chief describes the land as Māui’s fish and states that he will live on it until he dies. The effect of the quotation is to stress the profundity and longevity of the connection between Te Kawerau ā Maki and Te Wao Nui a Tiriwa. Conceptions of the ‘private’ and ‘public’ cannot invalidate and ought not to undermine mana whenua.

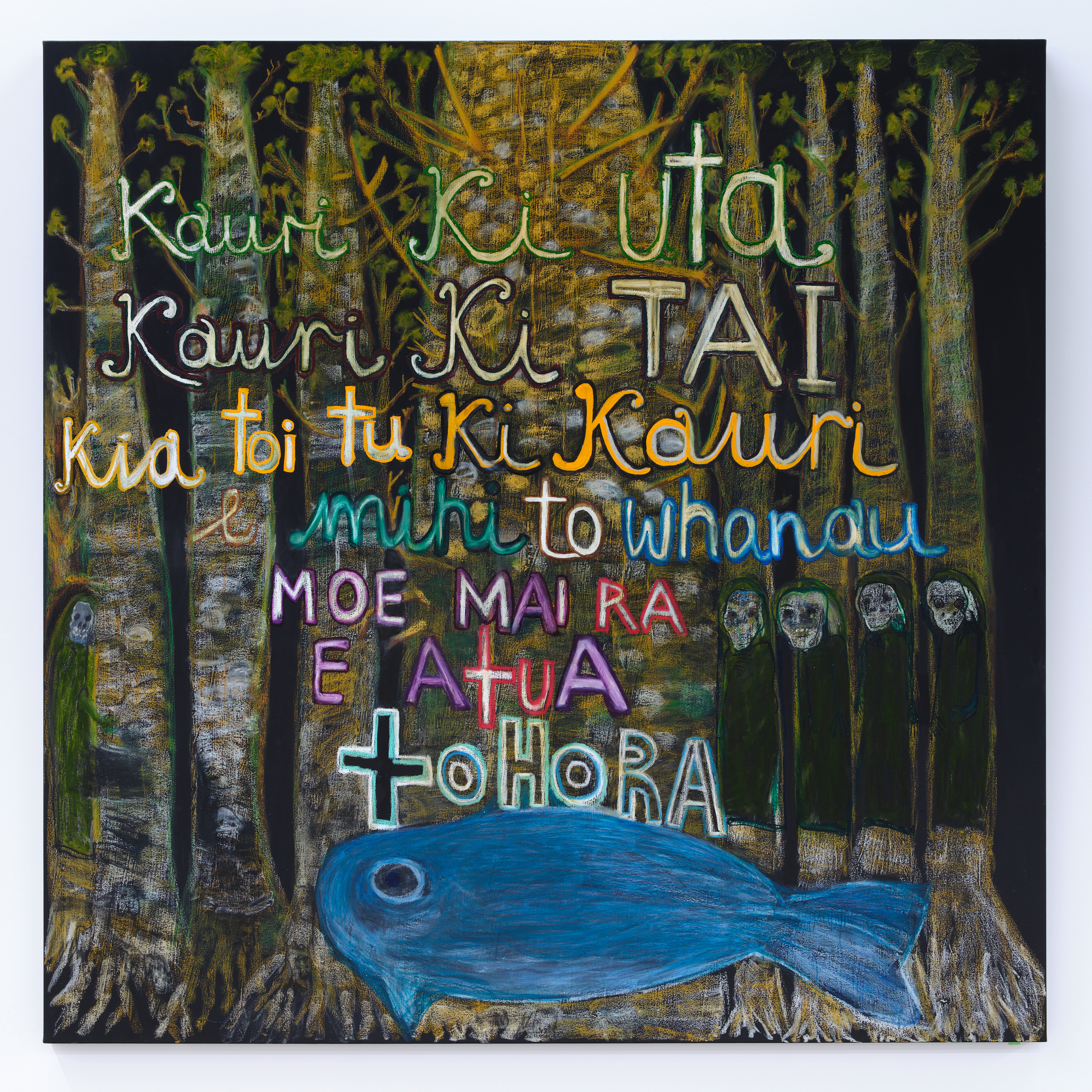

Emily Karaka, Moe Mai Rā, Tohorā, 2021. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

Another exploration of deep relationships is found in Moe Mai Rā, Tohorā. This lyrical work shows a tohorā, a whale, lying beneath Tāne Mahuta, the huge kauri in Waipoua Forest, further up the west coast of Te Ika-a-Māui. The tohorā, like the kauri, is an ancient and mighty being. In some accounts, the two are brothers, children of the god of the forest, Tāne Mahuta.[5] Tohorā bestowed on Kauri his scaly skin, while Kauri gave Tohorā his oil. Recently, whale blubber and bone have been posited as a potential treatment for kauri dieback.[6] Kauri and tohorā are our forebears, yet we have not always shown them due respect. The survival of both depends on our stewardship. It is a responsibility that Karaka feels and wants us all to feel.

I Bow My Head evokes an attitude of humility and of prayer. The painting centres on kauri, specifically those found at Parehuia. A small ‘67’ on the left-hand side marks the address of McCahon House on Otitori Bay Road. The number is attached to the sternpost of a waka that is also suggestive of a leaf-strewn way. (It is worth noting that both Te Kawerau ā Maki and Tāmaki Makaurau are sometimes referred to as Te Kei o Te Waka o Tainui, the stern of the Tainui waka.) As with Moe Mai Rā, Tohorā, the canvas is inscribed with a text of the artist’s own devising. Karaka describes what she sees around her: ‘The path covered with golden leaves and falling twigs no longer able to cling to blackend [sic] branches covered with grey green moss and your trunk splitting with no oxygen to breathe […]’

Emily Karaka, I Bow My Head, 2021. Photograph by Samuel Hartnett, courtesy of the artist.

The kauri depicted bear trails of weeping resin. Karaka comments that the scars are like the threads of a korowai, a cloak. The work thus ties into her long-held interest in korowai and whāriki as emblems of complex, intertwined relationships, including those between different people and those between humans and the wider world in which we exist. The final lines of text read, ‘I bow my head … e atua … Parehuia’. The precise meaning of the closing ‘Parehuia’ is not clear. It might simply record the place where the invocation is being made. It might signal that the kauri and the ancestor are both being addressed or are being addressed as one. It might indicate that it is Parehuia who is uttering the words—Parehuia the whare, Parehuia the tupuna, Parehuia the tohunga mahi toi.

Rāhui

Emily Karaka

29 April to 13 June 2021

Visions

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland

[1] Emily Karaka, ‘Tangi. Muriwai’, McCahon 100, McCahon House Trust, accessed 19 April 2021, https://mccahonhouse.org.nz/100/emily-karaka/.

[2] See Mike Baker, Jennifer Valentino-DeVries, Manny Fernandez and Michael LaForgia, ‘Three Words. 70 Cases. The Tragic History of ‘I Can’t Breathe.’, New York Times, 29 June 2020, accessed 19 April 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/06/28/us/i-cant-breathe-police-arrest.html.

[3] See ‘Archaeological Assessment: Proposed National Erebus Memorial site, Dove-Myer Robinson Park’, Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage, updated 15 April 2021, accessed 19 April 2021, https://mch.govt.nz/national-erebus-memorial/archaeological-assessment.

[4] See, in particular, Native Land Court, Important Judgments Delivered in the Compensation Court and Native Land Court, 1866–1879 ([Auckland]: Published under the direction of the Chief Judge, Native Land Court, 1879), 64: http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-NatImpo-t1-g1-g2-t6-body1-d7.html.

[5] Donna Kerridge, ‘What We Can Learn from the Stories of Kauri, Tohorā and Tīwaiwaka’, Spinoff, 3 December 2020, accessed 19 April 2021, https://thespinoff.co.nz/atea/03-12-2020/what-we-can-learn-from-the-stories-of-kauri-tohora-and-tiwaiwaka/.

[6] D’Angelo Martin, ‘Traditional Māori Medicine Could Be a Cure for Kauri Dieback’, Stuff, 5 June 2019, accessed 19 April 2021, https://www.stuff.co.nz/environment/113238540/traditional-mori-medicine-could-be-a-cure-for-kauri-dieback.