Art fairs are curious creatures. Whether you’re dealing with a lavish behemoth like Frieze London or a more modest entity like Auckland Art Fair, the general template tends to remain the same. A panoply of galleries gathered together for a short period of time, competing to see who can most successfully transform a basic booth into something special, memorable. A crush of people. The glossiest of works. Flimsy walls teetering under the weight of so many statement pieces. Critics love to hate them (commercialism in art—imagine that!), and, secretly, most gallerists do too. But they’re useful. As one-stop shops, they’re appealing to people who can’t be bothered schlepping all over the city, or who don’t have the means to travel beyond the same. They bring new eyes. They bring sales. The artist and the dealer have to pay rent like everybody else.

From the first, May Fair aimed to do things a little differently. While traditional fairs focus on long-standing galleries that show well-established artists, May Fair wished to provide a platform for early-career artists or those without dealer representation. Such artists are not necessarily absent from fairs. For instance, they regularly appear at Auckland Art Fair as part of the non-commercial ‘Projects Programme’ (with which I have been involved in the past) or in the designated emerging artist section. But they are seldom central. May Fair elected to concentrate entirely on this important group within the arts community, inviting various artists, artist-run initiatives, collectives, and curators from Aotearoa and the Moana (Pacific) region to participate. The approach makes the fair unusually interesting, since early-career artists make especially thought-provoking work. This year, there is also a heightened reward for participants. Unlike most fairs, which charge galleries for stands, May Fair is offering booth-holders a base fee (funded by Creative New Zealand), in addition to the promise of new audiences and sales.

The fair’s four organisers—Becky Hemus, Ophelia King, Nina Lloyd, and Eleanor Woodhouse—all have close ties to the ‘emerging artist scene’ in Aotearoa. They’re used to finding ways of making exhibitions and events happen, even when funding is limited. Their ambition and agility are high. Hemus and Woodhouse, for instance, recently established Wet Green, a gallery without a permanent address. Their inaugural project was a lavish performance by Hannah Maria Schmutterer, a German-born, London-based artist who has exhibited in various parts of Europe. May Fair, as originally conceived, was to take place in a large vacant building on Karangahape Road, and scheduled to coincide with Auckland Art Fair in May (the name May Fair puns on the month, as well as the swanky London suburb). But when the COVID-19 lockdown rendered that plan impossible, the organisers decided to turn the inaugural edition into a digital one.

May Fair Online launched on 30 July 2020 at mayfairartfair.com. It intends to provide a markedly unique experience, contrasting the ‘virtual exhibitions’ that cropped up during the recent lockdown—most of which were little to no different to the usual website presentations of galleries. Taking a cue from Spring 1883, an invitation-only art fair staged in the suites of hotels in Melbourne and Sydney, May Fair developed a simulated venue, replacing conventional three-walled booths with three-dimensional renders of ceilinged spaces, into which artworks could be inserted. (The renders put me in mind of mock-ups of the sort submitted by galleries to art fair selection panels, except considerably more finessed.) Each booth was furnished with fluorescent tube lighting, a window, and an octagonal oculus strikingly reminiscent of the skylights in one of Tāmaki Makaurau’s more esteemed galleries.

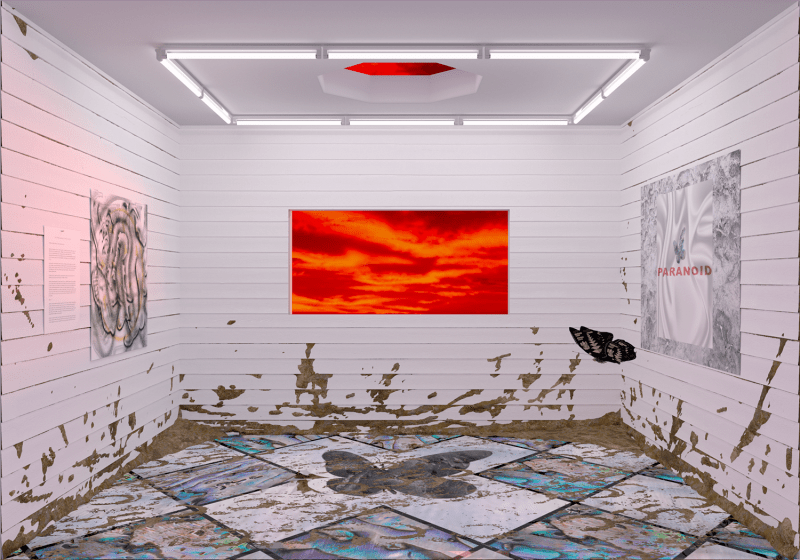

Stand-holders were given a great deal of latitude to personalise their spaces. Fanciful dressing elements could be introduced and landscapes out windows altered. The rooms themselves could be substantially reconfigured, floors tiled and soiled, walls broken apart—things that are not generally done at art fairs, not least because carpets and walls often need to be preserved for reuse. Animated elements could be added, turning the booths into little worlds unto themselves. The resulting May Fair Online wholly embraces its digital format, playfully leaning into a mode of presentation that is no longer strictly necessary in Aotearoa, since the COVID-19 lockdown has of course been lifted, but that could well become necessary again before very long.

The twenty booths in the fair are not showing all at once. Just four are visible at any given time, with the selection ‘refreshing’ each Thursday during the five weeks of the fair. This system means that visitors can dedicate time to the open booths, getting to know them individually, rather than feeling the need to triage and skip, as so often happens at physical fairs, where overload is chronic. Images of items for sale are included alongside the booth renders. Texts by leading writers—many early-career, like the artists—help unpack the projects. The fair also features online events, such as live readings and film screenings. This piece does not attempt to tackle all the components on offer. Instead, it homes in on six booths organised by an array of artists, curators, and spaces, and discusses a few of the elements of each. It represents a small introduction to a fair that does something special, memorable: creating an online experience that does not merely stand in for a physical fair but offers a distinctly meaningful, dematerialised alternative.

Tyson Campbell & George Watson

Appropriately enough, Tyson Campbell (Te Rarawa, Ngāti Maniapoto) and George Watson (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Mutunga, Moriori) first connected online rather than in person. Their May Fair presentation builds on a number of mutual interests. Both have engaged in collaborative work in the past (Watson, for instance, has previously partnered with Alex Laurie, also showing at the fair), and both have used décor and ornamentation to explore the enduring effects of colonisation on the cultural and natural worlds of Aotearoa. The artists lean into the fantastical possibilities of the digital context. The floor of their booth features squares of inlaid pāua, in a sort of luxe, local reimagining of chequered tiling. A butterfly is present as well. Campbell explains that it alludes to patupaiarehe, fairy-like forest beings. The walls are lined with wood panelling that makes reference to the villa (typically formed from ‘native timbers’), a symbol and symptom of settler domestication. Different registers of expression—the kitsch, the prestigious, the contemporary, the ‘traditional’—collide, inviting reflection on the ways in which culture in this country is and ought to be produced and consumed.

Campbell and Watson’s project is extraordinarily multifaceted. Mud slopped and splashed about their space—intended in part to suggest an abattoir—recalls the innumerable connotations of earth. I think of the media list for a 2018 work by Campbell at Artspace Aotearoa, which included ‘Tapu Ngāpuhi Mud’ and ‘unfired seemingly apolitical clay’. Horseshoe-prints evoke the horse as an element of agricultural and military projects, and as an animal valued by Māori (as it happens, the word ‘pāua’ can signify hoof). Campbell tells me that the prints indirectly allude to the cult tabi shoe by Maison Margiela. The overall vision is wryly dark, messing with clichés of nihilistic internet culture and the New Zealand Gothic alike. There is also earnestness and poetry, an embracing of the diverse and consonant forms of meaning-making in which we engage. Enchantment has many incarnations. A butterfly might hint at an aspect of te ao Māori, appear in a viral meme, or take the form of a tattoo fading on the wrist of a woman with an amethyst necklace. Campbell sums things up well, noting, ‘The concepts are quite large and the outcomes whimsical.’

Furniture Gallery

Parnell-based Furniture Gallery was established by Ben Martley towards the end of 2017 as Satchi & Satchi & Satchi (the space is situated just along from the Auckland branch of the international advertising firm Saatchi & Saatchi). It frequently highlights practitioners of exceptional talent while they are still in the earliest stage of their careers—that is, at art school. Furniture ‘alumni’ include the highly regarded Rea Burton and Claudia Kogachi, as well as several artists showing with other galleries at May Fair Online. The Furniture booth features work by Georgia Arnold, Olyvia Hong, Chris Peckham, and Nicholas Pound. The pieces are in a variety of media and displayed in a variety of manners. For instance, cast aluminium charms by Arnold are scattered, semi-camouflaged, among pebbles on the floor. Peckham’s contribution, a work in coloured pencil on paper, is embedded in a large block of ice on a glass shelf.

As is often the case with artists who show at Furniture, there is an emphasis on materiality. These are all works that cry out to be experienced in real life. A knobbly cast bronze apple by Hong practically demands a caress. Pound—whose work is luscious at the best of times—presents a trio of paintings that are all fingery, unctuous swirls of acrylic and oil. One is encrusted with a Batman magnet and a clutch of Monopoly buildings (these not only call to my mind London’s Mayfair but also nod towards Pound’s position as a dad very much involved in caregiving). All the paintings are marked by the sort of colour that is bound to change dramatically in response to different light conditions. There’s a real genius to Furniture’s selection. Pieces that were more graphic and less sensuous would not, I venture, have the same pull. Here, one has the impression of a richness yet to be fully consummated. One has to buy the works to experience them in their entirety—or at least plan a visit to the gallery. The online showroom as artistic dating app.

Lucy Meyle

Lucy Meyle is a multidisciplinary artist from Tāmaki Makaurau. Her work often explores ‘relationships between humans and the more-than-human’, and between human-made and naturally occurring entities. Earlier this year, she had a solo show at Enjoy in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. She presented a series of works that played with containers or coverings as diverse as seashells and synthetic upholstery, teasing out similarities—formal and functional—between things that might ordinarily seem far distant. A metallic mesh sleeve filled with ‘real and fake foods’ initially called to my mind environmentalist concerns, suggesting both foam protectors for mangoes and reusable net bags: rubbish and its alternative. However, when I registered the title, Snake’s Dress, the piece took on an amusing new identity as a serpent that had gorged itself on groceries. The show as a whole was marked by a distinct humorousness, relishing in the silly. Among the works was a fibreglass reproduction of a peanut husk, absurdly oversized and unutterably tactile (being a child of the nineties, I thought at once of the supermarket Big Fresh).

Meyle’s May Fair booth is no less playful. On an outdoor platform, she presents a pile of prop-like logs made of recycled cardboard and brown packing tape. They’re immediately legible as blocks of wood, but quite unrealistic. The avowedly fictive exhibition space multiplies the phoniness. Imitation logs digitally inserted into an imitation environment. Yet no one’s pretending otherwise. All mischief is out in the open. An animated element adds further theatricality. A snail glides along a log. Snails have appeared in various works by Meyle. They’re critters with multiple identities: bothersome (my lovely lettuces!), fragile (I think of threatened native snails as well as unsuspecting victims of night-time strolls), and important as decomposers. But, again, I’m getting distracted by ecological matters, losing sight of subtler details—not least points of commonality between log and snail. Both possess crunchy brown carapaces. Both are charmingly cartoonish. And both gesture beyond the bounds of the booth context, not only because they are facsimiles, but also because they are fellow entries in Meyle’s evolving catalogue of the curiously kindred.

Sione Tuívailala Monū

Sione Tuívailala Monū is an artist of Tongan heritage who has been attracting attention for some years now, both as a part of Pacific queer collective FAFSWAG (they are no longer a member), and in their own right. Their May Fair Online booth is strikingly elegant, decorated with a large coconut palm and a family of pigs seemingly sculpted out of marble. All is stark white, save for the works proper, a series of brightly coloured masks festooned with plastic flowers and strings of crystalline and pearlescent beads. The masks at once suggest performance and stand as fully realised pieces. Having seen similar works by Monū in the real (a pair of flowering clouds is on display in the office and reading space attached to the new Tautai gallery), I’m familiar with the ways in which they respond to light and the moving eye of the viewer. Beads glisten and sparkle. Petal tones glow, pulse. Even as they hang still on a wall, Monū’s pieces radiate energy.

The masks have a range of reference points. A crown-like example is marked with the name Kanokupolu, Monū’s village in Tonga (from which the nation’s royal family also comes), and the place in which the works were produced. They connect with Tongan ceremonial and celebratory costume that incorporates flowers (plastic is preferred when fresh flowers are not available or when a piece needs to be longer-lasting), affirming the continuity and adaptability of the culture. Furthermore, they invoke the notion of the mask as a means of transforming one’s personal identity. Sometimes, such a transformation takes place only for a limited time and in a particular space. And yet it can get at an essential and enduring flourishing. I look at the masks—presented in a glorious invented gallery, in public, and as treasures—and I feel a deep sense of joy. These are works that brim with variegated pride.

Parasite

Parasite, an appointment-only space on Karangahape Road—was founded this year by Daniel John Corbett Sanders, who has done much of late to highlight the low visibility of LGBTQIA+ art at Aotearoa’s larger institutions. The booth includes work by three artists from the community: Tash Keddy (some might recognise the name from a certain long-running medical soap opera), Ali Senescall, and Samuel Te Kani. In keeping with his enthusiasm for fucking with mainstream comfort, Sanders has radically transformed the booth template. One of the concrete walls of the space has been blown open, exposing a mesh of rebar. Rubble litters the floor. (The oculus remains overhead, but how long it will stay there is anyone’s guess.) Whether the ruinous state is the product of a righteous revolution or of an apocalyptic calamity born of a lack of revolution remains unclear.

The works are generally affordable, much more accessible than the usual art fair fodder. Their placement is careful, quietly resisting the chaos. Keddy shows a trio of poster prints suspended by chains. Senescall has a print on a wall and a video playing on a monitor that leans against a fragment of same. Te Kani is represented by a book of erotic fiction titled Daddy. I confess that I’m a bit of a Te Kani fanboy. He’s polymathic in talent, having produced compelling installation art, as well as all manner of texts: fictional, journalistic, and ‘reflective’ (the piece on Campbell and Watson’s May Fair collaboration is his work). He side-lines in writing personalised erotica, ‘epics that’ll make you

Balamohan Shingade

Independent curator Balamohan Shingade (formerly assistant director of Auckland University of Technology’s ST PAUL St Gallery) has put together a solo presentation of photographs by Chervelle Athena showing kauri in Trounson Kauri Park and Waipoua Forest. These trees, like those in other areas, are under threat from Phytophthora agathidicida, or ‘kauri dieback’, which is spread by humans tramping through bush areas, both for fitness and—ironically—in order to admire the trees themselves. Athena hopes that the photographs will encourage the cultivation of ‘a deeper reflective connection between humans and plants’, so that efforts to protect kauri, such as the rāhui placed upon the Waitākere forests by Te Kawerau ā Maki, will be supported with enthusiasm. There is a sense that Athena is extending on notions of the photographic image not as a discrete representation but as something vitally connected, an embodiment of the lifeforce of its subject.

Shingade’s booth design enhances the mood of respectful, even reverent, engagement with the natural world. He has created an entirely bespoke environment, a sort of sanctuary based on the buildings of Indian architectural practice Studio Mumbai, which resist sharp demarcations of interior and exterior, human and non-human space. (I’m also reminded of Waitākere houses from the twentieth century designed to embrace the outside world.) In a witty gesture, Athena’s photographs are seen on the walls of the pavilion and through the expansive windows. Warm light—seemingly dappled by the exterior trees and the timber window elements—falls across a concrete floor. Although digital, the space is attuned to, or keyed by, the natural environment, doubly different to the art fair booth one might ordinarily encounter.

The effect is powerful. Athena and Shingade summon the viewer to find the method for reverence most appropriate to the circumstances. If actually visiting a location entails the risk of causing serious damage, then it might be that engaging with photographs, renders, a fantasy space is not merely worthy but necessary. A related idea is implicit in May Fair Online as a whole. In times of crisis, whether created by a phytophthora or a virus or something else altogether, alternative ways of doing things must be found. The exciting prospect is that such alternatives might have enduring relevance, not because they replace the old ways (we’ll still want to see unctuous paintings and smell damp foliage), but because they offer a worthwhile extension. May Fair’s brilliance lies in both adding something different and appealing, and helping us to value more keenly material that we’ve long taken for granted.

*

Essay commissioned by Index and republished by Art Paper.

May Fair

30 July to 4 September 2020

mayfairartfair.com